You Can't Focus Group Your Way to Permission

Why researchers and startups are worlds apart on climate risk

This is part 2 in a short series on the narratives and permission space around climate interventions. Part 1 was Nature Abhors a Narrative Vacuum.

A few months ago I wrote about facilitating a breakout session on narrative and communications at a Climate Emergencies Forum workshop. There were serious people at that table, folks with real expertise in climate communications and policy, and we had a genuine conversation about how to share messages that actually resonate with what people care about. We all knew the common takes about how climate change never ranks high in voter priorities relative to things like economic affordability and healthcare. The outcome from the session—which I helped shape as facilitator—was that the field should do more demographic research, compile the results, and find ways to train the various organizations working on catastrophic climate risk to speak about these issues more effectively in a way that resonated more with what regular people care about.

I left feeling frustrated with myself as much as anything, and I think I understood why even in the moment.

From my experience in the startup and tech world, I’ve come to believe that if you want to reach large numbers of people about something important, you can’t rely on focus groups and message training alone. You need to lead strongly with a perspective rather than hedging everything into mush. You have to use the channels people are actually using, which means podcasts and YouTube and social media and newsletters, not just op-eds and position papers that circulate among people who already agree with you (though I think op-eds like this are helpful). And you need to engage with people as if they’re intelligent adults who can hold complexity in their heads.

The people at that workshop weren't wrong about what they proposed. Demographic research and communications training are useful things. But I kept feeling like there was a deeper issue that none of us were naming: we were approaching a permission problem with messaging tools. It's what the field knows how to do. It's also not sufficient.

The permission problem

A politician who wants to engage seriously with sunlight reflection or other climate interventions will face attacks from multiple directions at once. Conspiracy theorists will accuse them of pushing chemtrails. And environmental groups will warn about moral hazard and giving fossil fuel companies an excuse to keep drilling. Scientists who work on this stuff often avoid public engagement because it puts their careers at risk, and I’ve watched other scientists actively censor colleagues who try to raise these topics publicly.

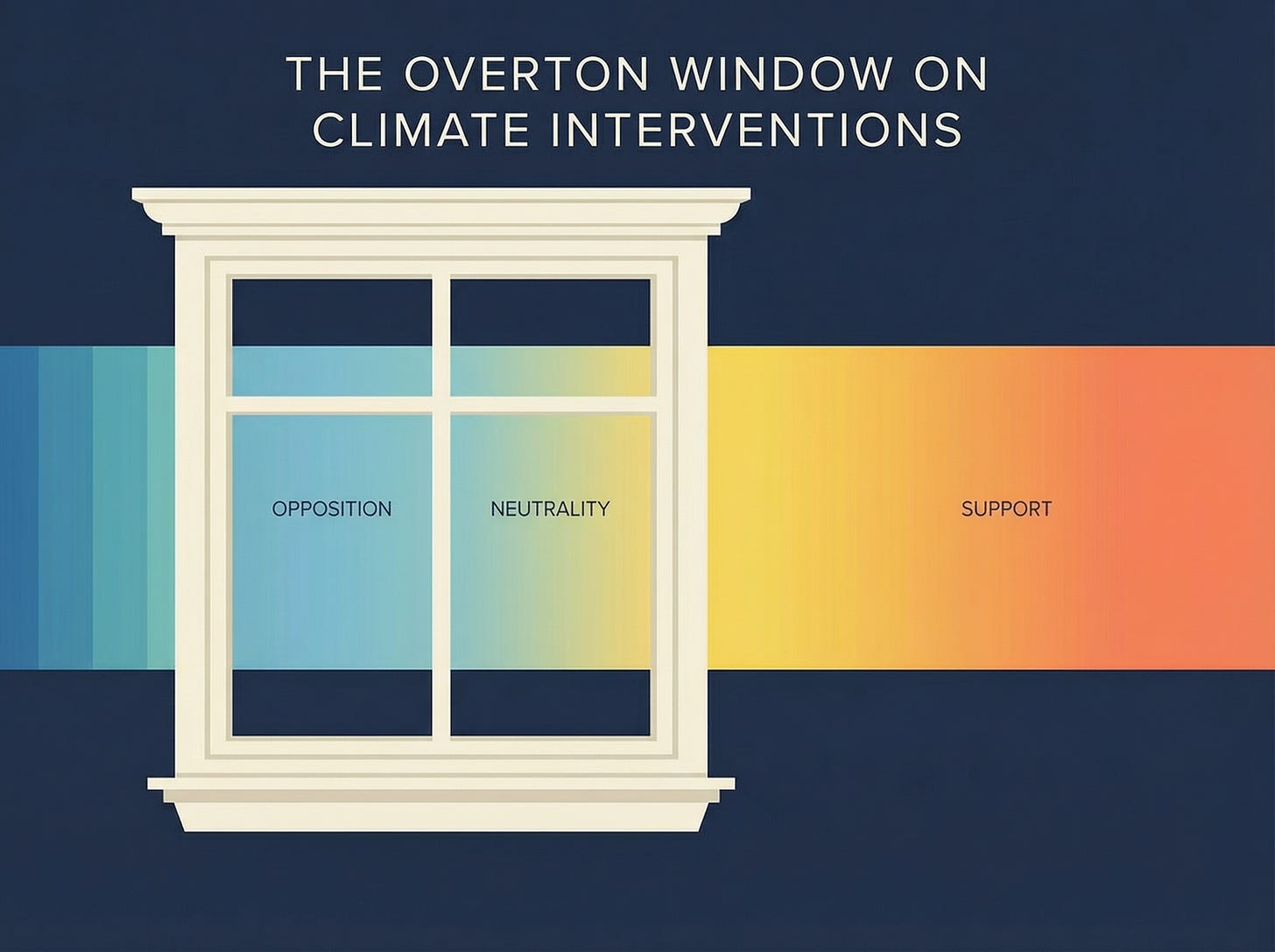

The Overton window for discussing interventions that respond to catastrophic climate risk currently runs from vociferous opposition to careful neutrality, and that’s the entire range of acceptable opinion. There’s almost no space for someone to say “I think we need to seriously prepare for these interventions” without facing professional consequences.

You can’t fix that with better messaging. No amount of demographic research will change the fact that taking a public position on this stuff can harm your career. Searching for just the right words won’t solve this. The real problem is that cultural permission to even have the conversation doesn’t exist.

Messaging is about finding the right words to make your position palatable within the current range of acceptable opinion. Permission-building is about expanding that range in the first place. They're different problems requiring different tools.

Two different worlds

I’ve been thinking about why this permission problem persists when the people working on climate interventions clearly understand it is real. And I think the answer is that this field operates almost entirely within a set of institutions whose tools aren’t suited to permission-building, even though they’re essential for everything else.

Call it World 1: academia, research institutions, policy organizations, international bodies, government agencies. This world operates through peer review and consensus-building and careful deliberation. It moves slowly on purpose, because when you’re trying to establish scientific credibility or develop governance frameworks for interventions that could affect the entire planet, moving slowly is appropriate. World 1 has also made genuine efforts toward global inclusion, with organizations like the Degrees Initiative funding researchers in the Global South so that climate-vulnerable nations can develop their own expertise rather than depending on wealthy Northern institutions to make decisions for them.

World 1 should be leading on climate interventions that respond to catastrophic risk. I believe that. The stakes are too high and the governance questions too serious for the move-fast-and-break-things approach. But World 1 cannot build cultural permission through its channels. Academic papers and institutional reports don’t shift what’s speakable in mainstream conversation anymore. Policy briefs don’t create the conditions where an elected official can engage with these topics publicly without getting destroyed from both sides.

Then there’s World 2, which is where I come from: tech, startups, venture capital, as well as podcasters, newsletter writers, YouTubers, entertainment, and the entire ecosystem of people competing for attention in digital media. World 2 moves fast and iterates constantly and thinks about distribution and audience-building in ways that would feel foreign to most researchers. It’s also where the vast majority of people actually encounter new ideas, including the policymakers and philanthropists and business leaders that World 1 ultimately needs to influence. When someone wants to get up to speed on an unfamiliar topic, they’re more likely to start with a podcast episode or a well-written essay than a literature review.

World 2 also tends to be heavily American in ways it doesn’t always recognize. The platforms are American, the venture capital is mostly American, and the cultural assumptions about how things should work are shaped by Silicon Valley. People building things in World 2 aren’t always thinking carefully about how their work lands in Bangladesh or Nigeria or Brazil.

For climate interventions responding to catastrophic risk, World 2 is almost completely empty. The serious work happens in World 1, which is appropriate. But the accessible channels where most people form their opinions are filled with conspiracy theories on one end and sensationalized startup drama on the other. Almost nobody is doing the work of translating World 1’s careful research into forms that can actually build cultural permission.

What happens when World 2 rushes in without understanding World 1

There are a few exceptions, and from where I sit, I don’t think it’s going all that well.

Make Sunsets has been launching high-altitude balloons releasing small amounts of sulfur dioxide, first in Mexico and then in the US. The logic is classic World 2 thinking: the crisis is urgent, institutions are moving too slowly, someone should just demonstrate that this technology works rather than waiting around for permission. The result has been backlash that makes World 1’s work harder. Mexico allegedly banned outdoor SRM experiments in response. The EPA sent inquiries (which Make Sunsets responded to, to their credit). People working in policy circles tell me that when they meet with congressional staffers about climate interventions, the first question they get is often “what about Make Sunsets?” and they have to spend precious time managing that conversation before they can discuss anything substantive.

At the same time, more people are aware of the potential to cool the planet through Make Sunsets' work. I've spoken with some of their customers, and they feel inspired and optimistic about the possibility of taking action on global temperature. That's a good thing. Creating hope and a sense of agency is a goal I share. Whether that tactical tradeoff is worth the governance backlash, I genuinely don't know.

Stardust presents a different kind of problem. They recently raised $60 million in venture funding to develop novel cooling particles. I can trace the logic of their decisions step by step, and each one makes sense in isolation:

Sulfur dioxide (for SAI) is a pollutant with health impacts and potential risk to the ozone layer, so why not engineer something better?

Philanthropic funding for this kind of work isn’t flowing at scale, so raise venture capital because that’s where the money is.

Venture capital requires returns on investment, so develop proprietary intellectual property that you can commercialize.

But the endpoint of that chain is a private company trying to own IP on planetary-scale interventions, which creates incentive structures that are fundamentally misaligned with the governance requirements for something that affects everyone on Earth.

The closest analogy I can find is nuclear weapons. Not because cooling particles are necessarily weapons (though they could be), but because the effects are inherently global. We wouldn't tolerate a venture-backed startup developing nuclear bomb capabilities and then shopping them to governments with assurances about responsible use. We built an entire international framework around the recognition that some technologies are too consequential for that model. Stratospheric interventions have a similar scope: release particles into the stratosphere and they circulate globally. There's no version of "one country deploys this for itself." The intervention is planetary by nature, which is what makes private IP ownership on the core methods so structurally problematic.

I recognize the counterargument: if everyone waits for governance frameworks to catch up before developing anything, we might wait too long. That's a real tension, and I don't have a clean answer for it. But there's a difference between private companies providing implementation services under public direction—building capacity that governance frameworks can eventually direct—and private companies developing proprietary control over the intervention itself. The latter inverts the relationship that legitimate governance would require.

I’m not attacking these companies or the people behind them. I understand why they made the choices they made, and honestly, a decade ago I might have made similar ones. But the pattern is World 2 actors getting frustrated with World 1’s pace and charging ahead without understanding why World 1’s slow legitimacy-building process actually matters. The backlash from these efforts makes the permission problem worse, not better. And the more this happens, the more climate interventions get framed in mainstream coverage as billionaire tech bros trying to hack the planet, which is political poison for the researchers and policymakers who need public trust to do their jobs.

The bridge that needs building

So here’s where I’ve landed after a year of trying to understand this ecosystem and figure out where I might contribute.

World 1 should lead on climate interventions responding to catastrophic risk. I genuinely believe that. But World 1 alone can’t build the cultural permission it needs to lead effectively, because its tools and channels aren’t suited for that work.

World 2 has the tools and instincts for building cultural permission, but it’s mostly not engaged with this space. And when World 2 actors do engage, they tend to make things worse by racing ahead of the legitimacy infrastructure that World 1 is trying to build.

The gap is World 2 work that’s genuinely in service of what World 1 needs. Not replacing World 1’s leadership, but enabling it. What we need is narrative work, accessible communication, and cultural content, all oriented toward creating the conditions where serious governance conversations can actually happen rather than getting derailed by controversy.

I come from World 2. I spent years building a carbon removal company and thinking about how to create markets and shift cultural narratives (and we were largely successful!) I’ve now spent the past year immersed in World 1 for climate interventions, learning from researchers and policy people and trying to understand what they’re doing and what they need. What I keep seeing is two worlds that barely talk to each other, and a permission problem that neither one can solve on its own. Both are needed!

Building that bridge is what I’m trying to do. I want to build the cultural permission that makes World 1’s leadership actually possible. I want to make this category of interventions feel like something serious people can discuss openly, rather than something that ends careers and attracts attacks from all directions.

Next week I’ll write about what that work actually looks like in practice: the stabilization framework, and what needs to exist to make it real.

Part 1 in this series:

Nature Abhors a Narrative Vacuum

In April of last year, an audience member at a Dr. Phil town hall asked RFK Jr. about “stratospheric aerosol injections” being sprayed into the skies—bromium, aluminum, strontium, she said, peppered on us every day. His response: “That is not happening in my agency. We don’t do that. It’s done, we think, by DARPA. And a lot of it now is coming out of th…

Part 3 in this series:

The Stabilization Framework

This is part 3 in a series on narratives and permission space around climate interventions. Part 1 was Nature Abhors a Narrative Vacuum. Part 2 was You Can’t Focus Group Your Way to Permission.

This and every other article I publish is free because I want these ideas to reach as many people as possible. Paid subscriptions are how I keep doing this work independently. They allow me to follow the research on climate interventions and meet the researchers, practitioners, founders, and policymakers shaping how this landscape evolves.

Paid members get access to our community chat, where we discuss the latest developments in climate interventions and make sense of them together. I’m sharing all the really interesting videos, papers, stories, and other links I’m coming across in there. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, I’d appreciate your support.