The Stabilization Framework

A new category of climate change responses

This is part 3 in a series on narratives and permission space around climate interventions. Part 1 was Nature Abhors a Narrative Vacuum. Part 2 was You Can’t Focus Group Your Way to Permission.

This article represents the synthesis of all of my research, reading, and conversations over the last twelve months. Here I am laying it all out for examination. I want to be challenged on where you think this gets things wrong or can be honed and improved. Please comment at the end with any thoughts or questions you have.

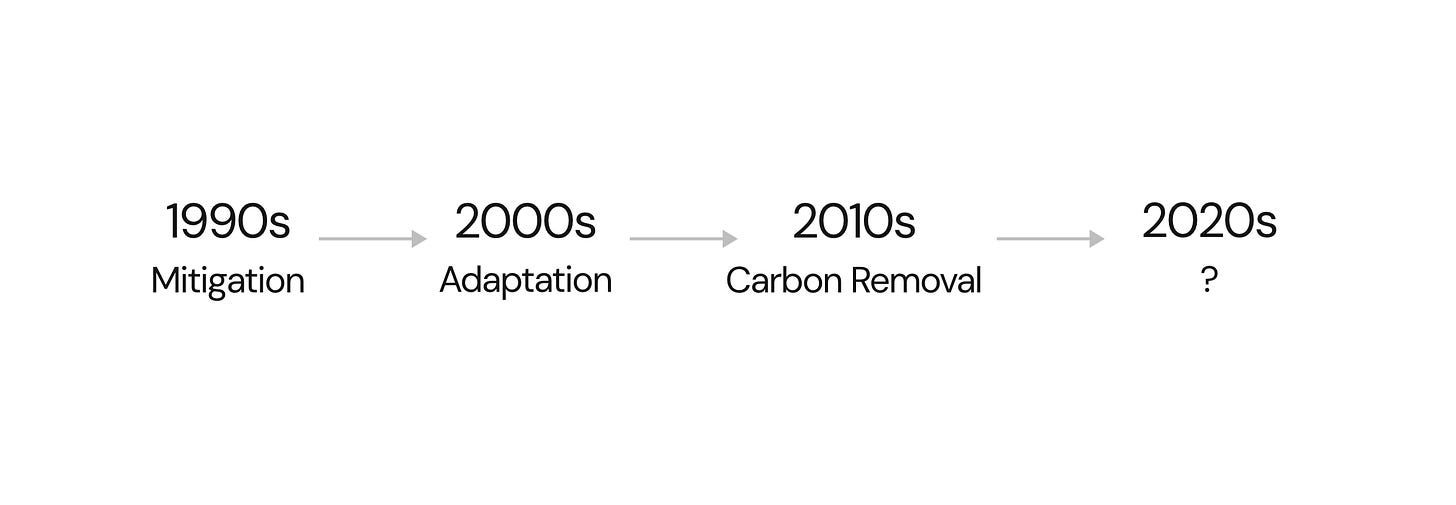

The climate toolkit keeps expanding, and each expansion has followed the same pattern: resistance, then reluctant acceptance, then obvious necessity.

In the 1990s, mitigation was the entire conversation. We should reduce emissions, transition to renewables, and stop burning fossil fuels. In the 2000s, adaptation entered the frame as it became clear that some warming was already locked in and we’d need to prepare for impacts regardless of how quickly we decarbonized. By the 2010s, carbon removal had forced its way into serious discussion, with the recognition dawning that even aggressive emissions cuts wouldn’t be enough to stabilize the climate without actively pulling CO₂ back out of the atmosphere.

I lived through the carbon removal debates. When I entered the field in 2015, even mentioning negative emissions drew accusations of enabling fossil fuel companies, of providing moral cover for continued drilling, and of dangerous distraction from the real work of cutting emissions. The moral hazard arguments were fierce. Over ten years, the conversation has shifted because the math became undeniable. Carbon removal went from heresy to IPCC pathways to corporate procurement programs to bipartisan legislation. The resistance didn’t actually vanish; it just got overwhelmed by necessity.

We’re at a similar inflection point now, not with a single technology but with a category: stabilization.

This article is a proposal for how to think about the range of climate interventions we’re going to need in the 21st century. These are interventions that go beyond reducing emissions and removing carbon to actively preserving stable conditions while those slower solutions scale up.

We face destabilizing systems everywhere we look. Not just in the climate itself but in the socioeconomic and political structures that depend on climate stability. Insurance markets are withdrawing from entire regions. Food systems around the world are stressed by drought and heat. Migration patterns are already shifting in ways that fuel political backlash. The capacity for democratic coordination is fraying under compound pressures. These are the stakes I laid out in my recent “Carbon Removal Won’t Scale in Time” presentation, and they’re why I think stabilization—as a frame—matters now.

In Parts 1 and 2 of this series, I wrote about the narrative vacuum around climate interventions and why the permission problem persists despite everyone recognizing it exists. This piece covers what I propose to do about it: adopt a stabilization framework that makes these conversations possible, and build the cultural infrastructure to support it.

What Stabilization Could Mean

I use “stabilization” deliberately. The word captures purpose—preserving conditions rather than engineering new ones—and it’s defensive rather than hubristic in its connotations. It also connects to something people already feel in their bones: the sense that systems are destabilizing all around us, that the ground keeps shifting, and that we need to arrest that slide before it overwhelms our capacity to respond.

“Geoengineering” sounds like playing God. “Solar radiation management” is jargon that makes normal people tune out immediately. “Restoration”—a term I’ve been asked about before—speaks to an acknowledged problem but begs the question: restore to what? And it misses a key insight. “Stabilization” names what we actually need right now: stable enough conditions for the long work of decarbonization and carbon removal to succeed. It’s not the solution itself but what enables the actual solutions to work.

When I talk about stabilization, I’m trying to capture a range of interventions that share a common purpose: preventing irreversible cascades of compounding catastrophic risks while the slower solutions scale. This could include:

Cooling interventions like stratospheric aerosol injection, marine cloud brightening, and cirrus cloud thinning.

Ice sheet preservation using thermosiphons to stabilize glaciers, seabed curtains, and other interventions to slow collapse that’s already underway.

Ecosystem protection, from localized cooling to protecting coral reefs to interventions that prevent Amazon dieback.

Tipping point prevention more broadly, from Arctic preservation, to permafrost management, to other efforts that keep feedback loops from triggering.

Regional weather modification and storm intensity reduction, though I know that category is contested and raises its own set of concerns.

Some of these interventions are further along in research than others. Some will face more governance challenges than others. Some people will object to including certain categories at all. The framework is a starting point for conversation, not a final taxonomy, and I expect it to evolve as more people engage with it.

What matters strategically is recognizing that these interventions don’t all have the same scale or level of complexity. Deploying nanobubbles to protect a specific coral reef involves fundamentally different governance challenges than global stratospheric aerosol injection does. Marine cloud brightening in a bounded region is different from interventions that affect the entire planet’s solar radiation balance. If everything gets lumped into a binary yes/no vote on “geoengineering,” we lose the ability to make progress on smaller interventions that might build trust, demonstrate responsible governance, and create capacity for larger ones later. The stabilization framework creates space for a spectrum of interventions differentiated by scope, reversibility, and governance requirements, rather than forcing an all-or-nothing choice.

The simple version of this framework is Reduce, Remove, Stabilize. None alone is sufficient. Reducing emissions won’t lower temperatures for decades; it only slows the rate at which they rise. Removing carbon dioxide won’t meaningfully affect global temperature until the second half of this century at the earliest, and only if we scale the industry far beyond anything we’ve achieved so far. Stabilizing conditions could work faster, but only makes sense as part of an integrated approach where we’re simultaneously addressing the underlying accumulation of greenhouse gases. We need all three tools working together. Stabilization is essential to make the other two possible to achieve.

The Precarity Trap

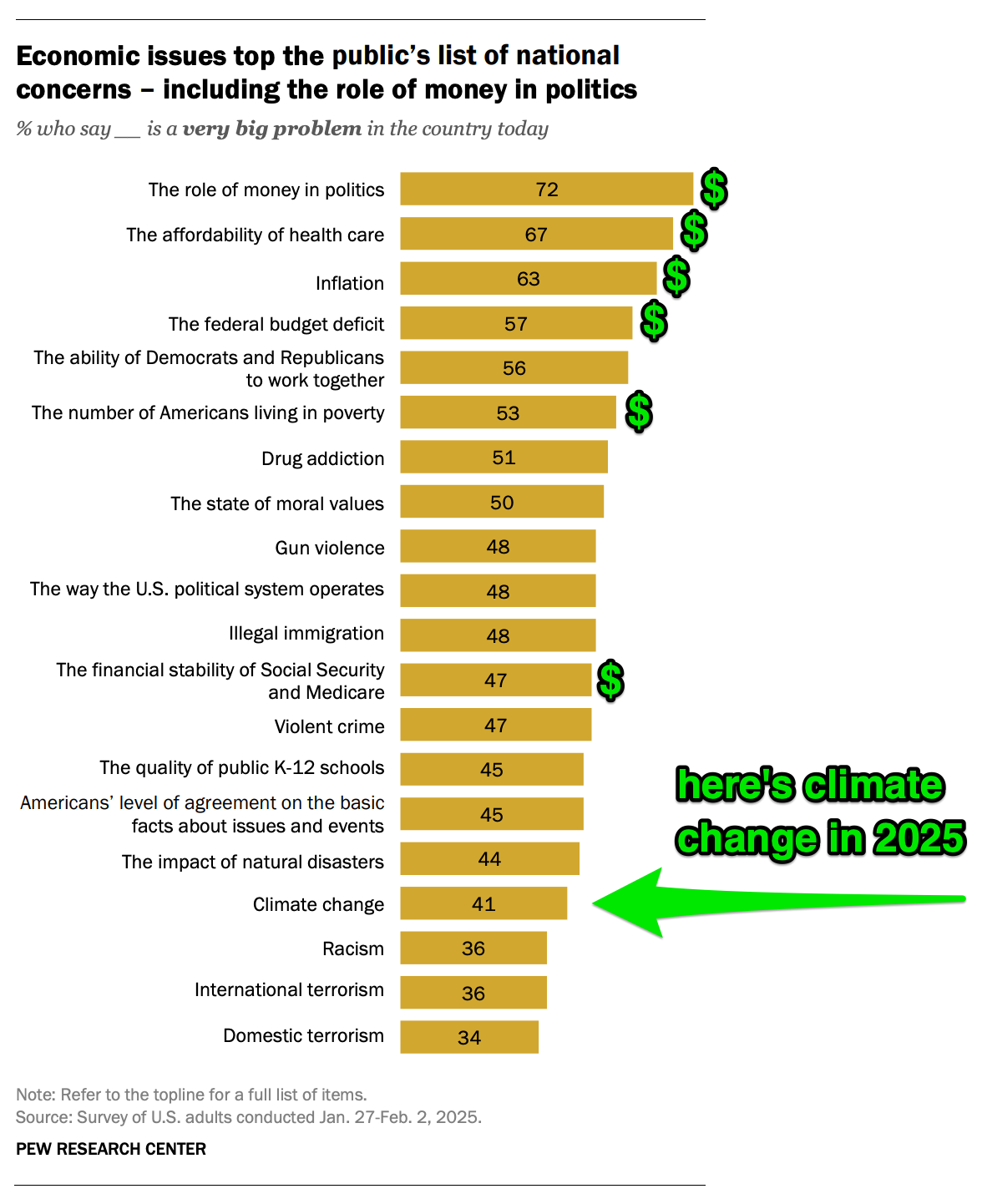

Countries with strong economic conditions tend to have more capacity for environmental action. They have cleaner energy policies, better environmental regulations, and more public support for long-term climate investments. But when affordability becomes the dominant concern, when economic anxiety rises to the top of political discourse, climate drops down the priority list. We’ve seen this play out in recent elections across the developed world, where inflation and cost of living overwhelmed nearly every other issue. And in much of the developing world, where economic precarity has always been the baseline, the bandwidth for long-term climate planning has never been abundant.

Voter polling consistently shows economic concerns like healthcare costs, inflation, housing, and job security dominate voter priorities by wide margins. When people are worried about affording groceries or medical care, when they’re choosing between prescriptions and rent, atmospheric carbon concentrations feel distant and theoretical. Climate becomes something you have bandwidth to care about when your immediate needs are met, and climate impacts are going to make economic conditions worse nearly everywhere.

Now consider what happens as those impacts intensify. Crop failures raise food prices. Extreme weather events disrupt supply chains and spike costs for basic goods. Insurance markets destabilize or withdraw entirely from high-risk regions, leaving homeowners exposed. And climate-driven migration—already underway, already reshaping politics—strains receiving communities in ways that fuel populism and political extremism.

This goes beyond just economic precarity into sociopolitical precarity. When migration becomes a wedge issue, when populist movements gain power by stoking fear of outsiders and promising to close borders, the political capacity for international cooperation on climate erodes. The parties and coalitions most hostile to climate action are often the exact same ones gaining ground from migration-driven backlash. The destabilization feeds on itself.

Think of it like a boxer. You can take some punches, you can absorb a bad round, recover between bells, and come back strong. But if you keep getting hit—round after round, with little time to catch your breath or reset—eventually you lose the capacity to continue the fight. You get knocked out not by any single blow but by the accumulation of damage you couldn’t recover from.

That’s what cascading destabilization means for our ability to respond to climate change.

Research on snowballing crises makes this concrete. After the 2021 Texas winter storm—which grew from weather event to power outage to water contamination to mental health crisis—researchers tracked impacts for nearly a year afterward. Using Crisis Text Line data, they found that total crisis conversations and thoughts of suicide increased substantially after the initial event and remained elevated for up to 11 months.

Populations hit by one disaster become less likely to rebound before the next one hits, because they can’t replenish economic and social capital between crises. Each successive shock finds people with fewer resources to cope, less resilience to draw on, and diminished capacity to respond.

Now apply this to climate at a planetary scale. If tipping points are triggered—think ice sheet collapse, ocean circulation pattern shift, permafrost thaw that releases stored methane, and/or ecosystems like the Amazon transitioning from carbon sink to source—each one depletes our collective capacity to respond to the next. These physical impacts will erode our ability to coordinate, to sustain political coalitions, and to maintain the economic stability that makes long-term planning possible.

One finding from the research on our responses to polycrisis stuck with me. Without deliberate effort, organizations and societies tend to regress to pre-crisis practices after the immediate threat passes. We can’t assume we’ll rise to the occasion. We can’t assume that escalating disasters will galvanize collective action rather than fragmenting it. Destabilization begets more destabilization, which undermines the capacity for coordination that climate response requires.

We can’t assume we’ll rise to the occasion. We can’t assume that escalating disasters will galvanize collective action rather than fragmenting it.

Given all this, why aren’t more people already working on stabilization interventions? Part of the answer is a persistent objection that deserves serious engagement.

Taking Moral Hazard Seriously

Critics of cooling interventions worry about moral hazard—that having a technological option will reduce pressure to decarbonize. Why do the hard work of transitioning away from fossil fuels if we can just cool the planet instead?

I don’t wave this away. The concern is legitimate because we’ve already seen fossil fuel executives use carbon removal as explicit justification for continuing their business model. The worry that the same thing could happen with cooling interventions, that fossil fuel interests could weaponize stabilization framing to delay transition, is real and needs to be addressed through how we govern these tools, not dismissed as ideological noise.

But I’ve come to believe there’s another risk we’re not weighing adequately, and it follows directly from the precarity trap I just described. If destabilization reduces our capacity to decarbonize, then the moral hazard calculation changes.

The political constituency for climate action requires some degree of economic security. The societal capacity for long-term coordination—the kind that is essential for energy transitions and international agreements—requires not being overwhelmed by cascading crises. If we let tipping points happen, we don’t just face worse climate outcomes in the physical sense; we face a world less capable of responding to them, a world where the political coalitions and institutional capacity and public bandwidth needed for decarbonization have been eroded by compound disasters.

Stabilization doesn’t let us off the hook. Rather, it preserves the conditions under which we can stay on the hook.

The logic runs like this:

Stabilization interventions preserve climate stability,

which preserves economic and social functioning,

which preserves the political space for sustained climate action,

which enables continued progress on decarbonization and carbon removal.

This path is a virtuous cycle where buying time creates the conditions for lasting solutions.

The alternative runs the other direction:

Uncontrolled warming triggers tipping points,

which cause economic disruption,

which fuels political chaos,

which reduces coordination capacity,

which allows more warming.

That’s a doom loop, and once we’re in it, the off-ramps get harder to reach.

The risk-risk framing (risk of moral hazard coupled with the risk of destabilization of society) doesn’t make moral hazard disappear, but it does contextualize it. Both risks are real. Responsible governance of stabilization interventions would need to explicitly couple any deployment with maintained and accelerated decarbonization. The goal is both/and, not either/or, and if stabilization were ever used as an excuse to slow the energy transition, that would be a failure of governance, not a vindication of the tools themselves.

I’ll be direct about where I’ve landed. I believe some form of cooling intervention is likely to be deployed within the next few decades, whether through coordinated international action or unilateral desperation by countries facing existential climate impacts. Which means the question isn’t whether it happens but whether we’re prepared to do it well or badly, whether deployment happens under conditions of careful governance and broad legitimacy or under conditions of panic and conflict.

If we were ready—if we had done the research, figured out how to manage risks, built the governance frameworks, established international coordination mechanisms, and developed public understanding—I would support deploying stabilization interventions today. The suffering that climate change is already causing, and will increasingly cause, argues for acting quickly once we know how to act responsibly. But the “if we were ready” in that sentence is doing a lot of work. We’re not ready. We need to get ready. And getting ready requires being able to have the conversation.

Building Cultural Permission

Over the past year, I’ve had dozens of conversations—probably fifty or more—with people working across the climate interventions space. They span researchers, governance experts, funders, communicators, entrepreneurs, and policymakers. The pattern that emerged is stark: there is not enough philanthropic capital flowing to this work, and public funding isn’t filling the gap either. The scale of resources going into understanding and preparing for these interventions is orders of magnitude off relative to the actual scope of the risk.

Good work is happening (I’ve written a guide to the organizations in this space) but all of them are resource-constrained. The entire field amounts to hundreds of millions of dollars for work on problems that will affect billions of people. The mismatch is staggering.

The funding bottleneck isn’t because funders don’t care about climate. Major foundations already pour resources into decarbonization, into adaptation, and into climate justice work. The bottleneck is that this particular space—cooling interventions and climate stabilization—feels too politically risky to touch.

If you’re a program officer at a major foundation that typically funds environmental work, climate interventions are either not on your radar at all, or if they are, you see them as too fraught to champion internally. There’s the chemtrails association. But more likely is your concern about moral hazard critique coming from environmental allies you respect. It feels exceptionally risky to be seen as enabling fossil fuel interests or techno-utopianism. All the dynamics I described in Part 1 of this series make advocating for this work feel like a career risk for anyone inside a foundation who might otherwise push for it.

So the funding stays on the sidelines, either ignoring the issue or waiting for someone else to go first. And without funding, the field can’t build the capacity for careful research, inclusive governance, and public engagement that would make these interventions actually viable. The permission problem and the funding problem are the same problem, each reinforcing the other.

This is what led me to conclude that cultural permission is the highest-leverage intervention point right now. Not because communications work is more important than scientific research or governance design—it isn’t—but because without cultural permission, the funding doesn’t flow. And without funding, the research and governance work can’t scale to what the problem demands.

This is what led me to conclude that cultural permission is the highest-leverage intervention point right now.

We have to make this permissible to discuss. Not because I’m advocating deployment tomorrow, but because we need to be doing the research, building the frameworks, and preparing for decisions that are coming whether we’re ready or not. If we can’t even fund the preparation, we guarantee that when the moment arrives, we’ll be caught unprepared and forced into bad choices under bad conditions.

How do you actually move an Overton window? Ideas are memetic—they spread through networks of people who influence each other, and large shifts in what’s considered acceptable don’t happen through academic papers circulating among people who already agree. They happen when a critical mass of influential people encounter an idea, engage with it seriously, and start talking about it with each other in ways that create social proof for further engagement.

Two recent examples have shaped my thinking about what this could look like.

The abundance agenda—articulated by Ezra Klein, Derek Thompson, and others—targeted a specific audience (the Democratic Party and the center-left policy world) but reached beyond it through a public book, podcasts, and sustained argument. The more people bought into the frame, the more palatable it became for policymakers to advance proposals that fit within it. The idea created permission for action that hadn’t existed before.

Leopold Aschenbrenner’s situational-awareness.ai had a similar effect in the technology community when it came out in 2024. A dense, comprehensive treatment of AGI timelines and their implications, it created a wave. Suddenly everyone in tech was reading it, discussing it, and taking seriously arguments that had been background noise before. The conversation moved from “I’ve vaguely heard concerns about this” to “we’re all actively engaging with this” in a matter of weeks. That shift from ambient awareness to active public discourse is what changes what’s politically possible.

We need something similar for climate stabilization: a comprehensive, accessible articulation of the situation that gives serious people a framework for engaging with it, something that can create a wave of understanding among the intelligentsia who shape discourse and the funders who resource work in this space.

That’s the hypothesis I’m working with. Shift what’s permissible to discuss, unlock philanthropic capital, and let that capital flow to the research and governance work that actually needs doing.

What’s Coming

In Part 1 of this series, I argued that we’re losing an information war we’re not even fighting. The narrative vacuum around climate interventions is being filled by conspiracy theorists—RFK Jr. endorsing chemtrails on daytime television, Nicole Shanahan’s “Dark MAHA Report” calling for constitutional amendments against weather modification, and content creators building audiences on paranoid fantasies about government poisoning programs. The serious people working on these questions are doing so in relative obscurity while the loudest voices spread confusion and fear.

Articles and academic conferences won’t win that war. We need a different approach.

I’m working toward what I’m calling the Stabilization Plan. This will be a comprehensive resource that combines the long-form nuanced writing this topic deserves with a strategic campaign to reach the people who shape discourse and seed these ideas where they can spread. It will have deep explanation of the climate math that makes stabilization necessary, honest assessment of each intervention option with its risks and uncertainties, direct engagement with the governance challenges we’d need to solve, and storytelling that helps people see what responsible deployment could actually look like—as well as what uncontrolled destabilization looks like if we don’t prepare.

The goal is to create an artifact around which we can orient the conversation I keep insisting we need to have, something designed from the start to reach the people who shape discourse, and through them, the funders and policymakers who can resource the work and create the political space for action.

When trying to launch a major influencing campaign, you don’t do it into a void. You build toward a moment, you prepare the ground, and you make sure when you ask people to engage they have something substantial to engage with. That’s what the Stabilization Plan will be.

We have some very important choices to make in the next few years that are going to impact outcomes on Earth for the next several centuries. We must build the cultural infrastructure that makes responsible action possible before catastrophe forces rushed and reactive decisions that lack the legitimacy that comes from inclusive deliberation.

This article—this whole series—represents the synthesis of many months of research, reading every book I could find on this topic, conversations with dozens of people working across the ecosystem, and sustained effort to think through the problem in public and get feedback. It’s my perspective, developed through immersion in this space, and it’s where I’ve landed after all that work. I expect it to evolve as I learn more and hear from others.

What I want now is feedback. Does stabilization as a framework resonate? Does this way of thinking about the problem help clarify what needs doing? What am I missing, what am I getting wrong, what objections haven’t I adequately addressed?

If this resonates with you, please share this article. The whole point is that these ideas need to spread beyond the small community already engaged with climate interventions. Permission gets built through ideas moving from person to person until a critical mass of people are thinking about them.

The community working seriously on climate interventions remains small relative to the scope of the problem. The gap between what needs doing and who’s doing it is immense. But the conversation is expanding. If you’ve read this far, you’re now part of that expansion.

The full Stabilization Framework series:

Nature Abhors a Narrative Vacuum

The climate intervention conspiracy theorists aren't coming. They're already running things. Who's going to fill the narrative vacuum?

You Can't Focus Group Your Way to Permission

Climate scientists and tech people speak different languages. The gap between them is where conspiracy theories thrive.

This and every other article I publish is free because I want these ideas to reach as many people as possible. Paid subscriptions are how I keep doing this work independently. They allow me to follow the research on climate interventions and meet the researchers, practitioners, founders, and policymakers shaping how this landscape evolves.

Paid members get access to our community chat, where we discuss the latest developments in climate interventions and make sense of them together. I’m sharing all the really interesting videos, papers, stories, and other links I’m coming across in there. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, I’d appreciate your support.

Dear Paul,

Thank you for this astute strategic proposal. I entirely agree with your framing of stabilisation as the key agenda. How stability could be achieved raises a series of difficult political problems. Stability was the core concept used by Deng Xiao Ping to enable China’s transition to a modern market economy, on the premise that without stability nothing is possible. As such, stability appears to be anathema to the climate action movement, who want to destabilise and destroy the fossil economy in order to build a renewable economy on its ashes. Climate stabilisation requires economic stability, which requires alliances with the fossil economy. The constituencies of support for climate stabilisation are therefore to be found outside the climate action movement, and instead should be sought among large industries that face commercial risk from warming.

Where I think your framework still needs a harder political pivot is around the “non-substitution” idea. In principle, yes: we do not want stabilisation to become an excuse to abandon decarbonisation and removal. In practice, the pace of physical destabilisation this century, especially the apparent decadal doubling of darkening and the rapid worsening of Earth’s energy imbalance, does not give us the luxury of making cooling conditional on an emissions coalition that does not yet exist. The conditionality risks preserving the very polarised paralysis that is now stymying action.

A Deng-style approach suggests a different sequencing: stabilise first, then deepen reform. In his memorable phrases, "Cross the river by feeling the stones," and "Black cat, white cat, catch mice, good cat." Applied to climate, that means making cooling the primary macro-stabilisation policy, with carbon action recast as the exit strategy from cooling dependence rather than the entry ticket that blocks deployment.

So instead of “non-substitution”, I’d propose a principle of non-abandonment. Cooling cannot be contingent on accelerated decarbonisation, because that keeps stabilisation hostage to the culture war and to veto players. Removing the excess greenhouse gas burden is not abandoned, it is written into the charter as the funded pathway to reduce long-run cooling dependence, manage termination risk and address ecological stability.

This reframing does not deny the moral hazard critique. It answers it structurally, by recognising the inertia, power and wealth of the fossil economy and hardwiring the exit ramp into the institution from day one, rather than by imposing a political precondition that prevents stabilisation from ever starting.

What is needed is a stability corridor, a defined safe operating range for the climate system and the human systems that depend on it, expressed in measurable indicators with upper and lower bounds (or rate limits), plus clear trigger points for action. A commitment to keep conditions stable enough for civilisation to keep working can enable a realistic assessment of issues around substitution. A stability corridor sets measurable guardrails for climate hazards and socio-economic impacts, with published trigger points and adjustment rules. It shifts the debate from ideology to results: like Deng’s ‘black cat, white cat’ test, the only question is whether a policy ‘catches mice’ by keeping the system inside the corridor fast enough to prevent cascading instability.

Concretely, a stabilisation doctrine could look like this:

Mandate a stability corridor: define objective indicators of system risk (food price volatility, insured losses, infrastructure failure rates, heat mortality, conflict displacement, etc) and target a corridor that protects economic and social functioning.

Portfolio not binary: treat interventions as a spectrum differentiated by scope, reversibility and governance difficulty, with staged learning rather than an all-or-nothing referendum

Cross the river by feeling the stones: bounded pilots, measured outcomes, rapid iteration, scaling only as monitoring and legitimacy prove out

Build legitimacy through transparency: open monitoring, independent auditing, published adjustment rules, clear triggers and clear failure modes, international coordination to reduce unilateral panic dynamics

A capitalist stability compact: be explicit that the aim is to preserve state capacity and economic continuity while the deeper transition is sequenced. Put the natural buyers up front: insurance and reinsurance, agriculture, shipping, infrastructure finance, sovereign risk managers, coastal real estate, supply chain heavy industry

Fund the exit strategy: allocate a fixed share of stabilisation funding to carbon removal, observation systems and adaptation, with a published pathway for reducing reliance on cooling as atmospheric CO₂ is eventually drawn down

Plan an Albedo Accord modelled on the Montreal Protocol, with narrow defined technical mandate to cool the Earth with safe and effective methods

This is not a plea to “go slow” on carbon just because we like fossil fuels. It is a recognition that, politically, a rapid forced contraction of the fossil economy is currently treated as an existential threat by large parts of the capitalist system and by many voters. If stabilisation is framed as contingent on that contraction, stabilisation will likely be blocked or delayed until crisis forces chaotic action. A stabilisation program worthy of the name should be designed to avoid panic governance by building an actionable coalition now around shared interest in economic stability.

If you are open to it, I’d love to see a follow-up post that tackles this question head on: what constituency can actually carry stabilisation to scale in the real world, and what doctrine avoids making stabilisation hostage to decarbonisation polarisation while still preventing permanent dependence.

Paul, you continue to do some of the most thoughtful and important work around.

I very much look forward to each of your posts and after some reflection I will respond as you requested in some detail.

In the meantime since you mentioned seabed curtains and ecosystem restoration

here are two conversations I recently moderated on these important subjects.

The first is on the audacious effort to research the possibility of erecting a seabed curtain to slow the melting of the so-called Thwaites Doomsday Glacier.

One of our speakers Dr David Holland of NYU spoke directly from deck of the research vessel off the coast of Antarctica!

https://youtu.be/SasKEzVkk7A?si=YKx9BKT3qkVxbJXJ

This next video is a conversation with the co-authors of “ Cooling the Climate, How to Revive the biosphere and cool the Earth within 20 years “ a book that makes the case that large scale ecosystem preservation and restoration could directly cool the climate particularly if focused in the Amazon.

https://youtu.be/Co7eigqN2d8?si=IhfawpmIF9X5NLT5