Nature Abhors a Narrative Vacuum

In April of last year, an audience member at a Dr. Phil town hall asked RFK Jr. about “stratospheric aerosol injections” being sprayed into the skies—bromium, aluminum, strontium, she said, peppered on us every day. His response: “That is not happening in my agency. We don’t do that. It’s done, we think, by DARPA. And a lot of it now is coming out of the jet fuel.” He promised to do everything in his power to stop it, and said he was bringing on someone whose entire job would be to investigate and hold people accountable.

That’s the United States Secretary of Health and Human Services endorsing the chemtrails conspiracy theory.

In July, his former running mate Nicole Shanahan published what she called the “Dark MAHA Report on Geoengineering,” sourced to an anonymous whistleblower with supposed high-level security clearances. The report calls for a constitutional amendment(!) “guaranteeing the right to unaltered weather in America” and conflates legitimate scientific research on cooling interventions with secret government poisoning programs. It’s been amplified across conspiracy networks as vindication for what the chemtrails crowd has been saying all along.

I know we already know this about many other aspects of the Trump administration, but it needs to be said about this too: the conspiracy theorists aren’t coming. They are already running things.

The narrative vacuum

There’s a vacuum right now around cooling interventions, and it’s getting filled, just not by the people doing careful work on these questions.

When most people first encounter the idea that humans might deliberately cool the planet, where do they encounter it? Possibly chemtrails videos on YouTube. Or maybe the recent wave of coverage around Stardust, the startup that announced a $60 million funding round and got written up in the New Yorker, Politico, the Atlantic, and MIT Tech Review. The stories focus overwhelmingly on controversy: will they actually do this, should anyone be allowed to, who decides, what could go wrong, etc. Controversy drives clicks, so controversy is what gets covered.

Meanwhile, there are hundreds of researchers doing diligent, rigorous work. The Degrees Initiative is building research capacity in the Global South so that climate-vulnerable nations can develop their own scientific expertise on these questions rather than depending entirely on research from wealthy Western institutions. SRM360 tracks developments across the field and creates educational resources. The University of Chicago’s Climate Systems Engineering initiative is advancing the underlying science. Reflective is building knowledge infrastructure to inform decisions about stratospheric aerosol injection. Both the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering and the Centre for Future Generations are working on governance frameworks to ensure these decisions get made legitimately. Operaatio Arktis is working with Nordic governments to address Arctic tipping point risks.

None of this gets the coverage. Journalists gravitate toward Make Sunsets launching balloons in Mexico, city councils shutting down marine cloud brightening experiments, and RFK Jr. making wild claims on daytime television. The people trying to carefully understand the science and build appropriate governance? They’re working in relative obscurity while the vacuum fills with something else.

I don’t actually think it’s a problem that conspiracy theorists exist. I don’t buy into the idea from the last 10 years that we would be better off if we could just “prevent misinformation.” Conspiracy theorists have always existed and always will.

The actual problem is the absence of an accessible alternative—a positive vision for what responsible cooling interventions might look like that ordinary people can understand and evaluate. Without that, conspiracy thinking becomes the default frame, because it’s the only frame available.

The trust vacuum pattern

COVID showed us how this works.

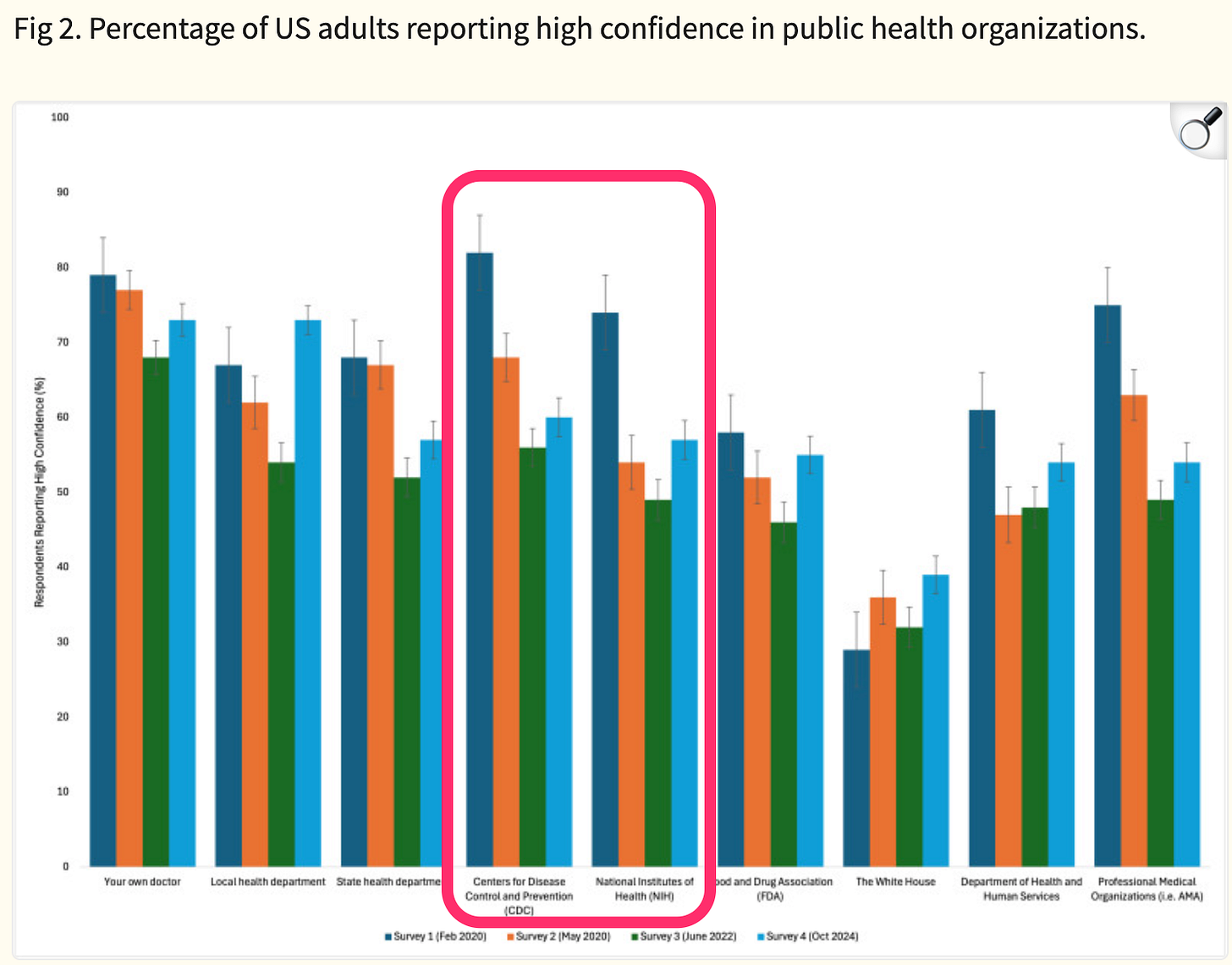

In the early months of the pandemic, US public health institutions made choices that turned out to be catastrophic for trust. Officials told people masks wouldn’t help while internally working to preserve supplies for healthcare workers. Vaccine messaging shifted from “prevents infection” to “prevents severe disease” to eventually just “prevents severe outcomes”—without ever clearly acknowledging what had changed or why. The message that vaccines would prevent transmission was used to justify policies long after we knew it wasn’t really true. Questions about whether the virus originated in a laboratory were dismissed as conspiracy thinking before eventually being treated as legitimate scientific inquiry.

I got vaccinated, I wore masks for a long time, and I’m not trying to relitigate every decision. But the pattern that emerged wasn’t just “difficult calls in a fast-moving crisis.” It was institutions that didn’t update their public messaging even when they had better information, that kept policies in place past their justification, that seemed to treat the public as something to be managed rather than informed. Whatever the intentions, the result was a trust vacuum. And that vacuum got filled by people positioning themselves as truth-tellers against a lying establishment. RFK Jr. had been an anti-vaccine activist for years, but the pandemic gave him a massive platform and a narrative that resonated: they lied to you about masks, they lied to you about vaccines, they lied to you about the lab leak, what else are they lying about?

Vaccine hesitancy is higher now than before COVID. The person who built that platform is running the country’s public health agencies, and he’s not just pushing anti-vax theories—he’s pushing chemtrails theories too, from a cabinet position, on national television.

The instinct to stay quiet

There’s a wariness in the climate interventions community about public engagement, and I’ve sensed it in conversations even when nobody states it directly.

These are genuinely complex decisions that require careful deliberation, so the wariness does seem somewhat prudent. Researchers need space to think through problems without being shouted at by people who don’t understand what they’re studying. Going too public too fast risks politicizing the issue before the science is mature enough to withstand political pressure. And the chemtrails problem is real. Any public discussion risks amplifying conspiracy theories rather than displacing them.

There’s also serious academic work on how to do public engagement well. There are methodologies for informed deliberation, frameworks for including affected communities, and research on what kinds of communication actually build understanding rather than backlash. That work is valuable and I would like to see more of it happening. But there’s a difference between a careful community engagement process and what I’d call public leadership: making an affirmative case about what the situation actually is and what we’re proposing to do about it.

There is a strong argument that these intervention decisions will ultimately be made by elite institutions—governments, international bodies, research consortiums—not through popular referendum. That’s how representative democracy works. The fastest path to good policy might run through institutional channels, not public campaigns.

But this logic has a gap: working through institutional channels doesn’t prevent public conversation. It just means that conversation happens without input from the people who understand what they’re talking about.

What happens when you cede the field

The public conversation happens regardless of whether researchers participate in it.

It fills with RFK Jr. on Dr. Phil. It fills with Nicole Shanahan’s absurd Dark MAHA Report. It fills with state legislators in Tennessee and Florida passing bills to ban “geoengineering” based on chemtrails conspiracy theories rather than any understanding of what researchers are actually studying. Meanwhile, the only mainstream coverage of actual climate intervention work comes when a startup raises money. The Stardust $60 million round got written up everywhere, while the steady work of research institutions goes largely unreported.

This isn’t a criticism of researchers for focusing on research, or of institutions for working through institutional channels. That’s their job, and they’re doing important work. The gap I’m identifying is a different role that nobody is filling. This is the work of making an accessible, affirmative public case for why we need to be studying these interventions and what a responsible path forward might look like.

And the people in those institutions consume accessible media too. Policymakers and funders listen to podcasts on their commute, read newsletters and Substacks, scroll social media like everyone else. When someone wants to understand a new topic, they might very well start with a podcast episode or a well-written essay, not a literature review. Working through institutional channels and communicating through accessible channels aren’t mutually exclusive—and the second can actually support the first.

What leadership looks like

I recently watched Deep Impact (for the first time!), and I was struck by the depiction of Morgan Freeman as president facing an extinction-level asteroid. He has to tell the country that civilization might end. He doesn’t hide it or downplay it, but he also doesn’t just deliver bad news and walk away. He lays out what the government is doing. He’s honest about uncertainty. He treats the public like adults who can handle hard information when it’s delivered with clarity and compassion and paired with a plan.

That’s what I want to see on climate interventions. Honesty about the threat and what we don’t yet know, paired with a clear articulation of what we’re proposing to do about it.

We’re obviously not getting that from the current administration. But leadership doesn’t have to come from government. Researchers like David Keith and Daniele Visioni already speak plainly about what they’re learning—that’s not the gap. The gap is in making an affirmative case for why we’re going to need these interventions, not just explaining the research. It’s the difference between “here’s what we’re studying and here are the uncertainties” and “based on what we know about tipping points and timelines, we need to be preparing for large-scale climate interventions, and here’s what a responsible path forward looks like.” That second message is what’s missing from public discourse, and it’s hard for researchers in institutional positions to deliver it.

That leadership also has to be genuinely global. Right now, the vacuum is being filled by American culture-war insanity. It’s our conspiracy theorists, our political circus, our tendency to turn everything into content for online fights. That’s a problem for the whole world, because climate change affects everyone and any interventions would too. The nations most vulnerable to climate impacts—the ones who will suffer the worst consequences of both continued warming and any interventions we might pursue—should have voice in these decisions precisely because they bear the most risk. The people who will live with the consequences have a stronger claim to shaping the decisions than those who caused the problem and will be more insulated from its effects. A leadership vacuum filled by US conspiracy theorists isn’t just an American failure. It’s a failure of the entire global conversation that needs to happen.

Why I keep talking about stabilization

We need language for this that isn’t captured by either conspiracy theorists or techno-utopians.

“Geoengineering” is loaded. It sounds like playing God, and it gets conflated with everything from weather modification to chemtrails to Bond villain schemes. “Solar radiation modification” is accurate but it’s jargon, the kind of term that makes normal people tune out immediately. Scientists talk about restoring “Holocene-like conditions,” which is precise but means nothing to anyone who isn’t already deep in climate science.

I’ve written before about why stability is the frame I keep returning to. What we actually want is stable conditions—the kind where the massive work of decarbonization and carbon removal can succeed, where supply chains and insurance markets function, where we’re not constantly responding to cascading crises that make long-term planning impossible.

So I use a simple framework: reduce, remove, stabilize.

Reduce emissions through decarbonization and the energy transition. Remove carbon dioxide through nature-based approaches like forests and soil, as well as engineered solutions like direct air capture, enhanced weathering, and ocean-based methods. Stabilize conditions through cooling interventions, ice sheet protection, ecosystem preservation, and whatever else it takes to prevent tipping points from cascading while the other two tools scale up.

None of these alone is sufficient. Reducing emissions is essential but won’t lower temperatures for decades or even centuries—it only slows the rate of increase. Removing carbon is essential but won’t meaningfully affect temperature until the second half of the century. Stabilizing conditions could work faster, but only makes sense as part of an integrated approach where we’re also addressing the underlying accumulation of greenhouse gases. We need all three working together.

The stakes

We can’t afford to let the RFK Jrs of the world own this narrative by default.

That’s what happens when people who understand the science stay in insider channels while conspiracy theorists dominate the accessible ones. It’s what happens when the only public-facing stories are about controversy and when the people doing serious work on climate interventions don’t feel empowered to make an affirmative case for what they’re studying and why it matters.

The researchers and governance experts working on these questions aren’t doing anything wrong. They have roles and constraints and theories of change that make sense for their positions. Academic institutions are unlikely to directly advocate for cooling interventions. Research programs need to maintain credibility.

The gap I’m pointing to isn’t their failure though. What I’m trying to point out is an opportunity that nobody is filling. Almost no one is doing narrative work in accessible channels. Almost no one is building the cultural permission space that would make it easier for everyone else to do their work.

That’s what I’m building. Not a campaign to convince people of a particular policy outcome, but an effort to make it possible to have honest conversations about the full range of climate interventions before crisis forces decisions that haven’t been thought through.

What does building that actually look like in practice? It turns out the answer depends a lot on which world you’re operating in. There are two very different ecosystems with different logics for how change happens, and they barely talk to each other. More on that in my next post.

Part 2 in this series:

You Can't Focus Group Your Way to Permission

This is part 2 in a short series on the narratives and permission space around climate interventions. Part 1 was Nature Abhors a Narrative Vacuum.

Part 3:

The Stabilization Framework

This is part 3 in a series on narratives and permission space around climate interventions. Part 1 was Nature Abhors a Narrative Vacuum. Part 2 was You Can’t Focus Group Your Way to Permission.

This and every other article I publish is free because I want these ideas to reach as many people as possible. Paid subscriptions are how I keep doing this work independently. They allow me to follow the research on climate interventions and meet the researchers, practitioners, founders, and policymakers shaping how this landscape evolves.

Paid members get access to our community chat, where we discuss the latest developments in climate interventions and make sense of them together. I’m sharing all the really interesting videos, papers, stories, and other links I’m coming across in there. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, I’d appreciate your support.

Really sharp piece. The COVID parallel is spot-on and kinda scary when you think about where we're headed. I've been trying to explain this stuff to non-technical folks and the reduce-remove-stabilze framework is way clearer than anything I've seen. Honestly think the bigger problem is most researchers still dunno how to bridge institutional work with public comunication, even when they see the gap.