How to Learn Everything You Need to Know About Climate Cooling

A Resource Guide for Getting Informed on SRM and Solar Geoengineering

I. Introduction

I used to believe we could solve climate change through emissions reduction and carbon removal alone. We’ve made fantastic progress making renewable energy cheap and widely available—but we haven’t cut back on the fossil fuels we’re burning. The Paris Agreement isn’t delivering the transformations we need on the timescale that matters.

And carbon removal? Despite 15+ years and billions of dollars invested, it remains little more than a cottage industry. Reaching gigaton-scale by 2025 seemed possible to me in 2015. It didn’t happen. My experience building and then winding down Nori showed me the challenges of scaling with painful clarity. We remain many orders of magnitude away from the pace we need.

The solution to climate change hasn’t changed: decarbonize as much of the economy as possible, remove over 1.5 trillion tonnes of legacy carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and oceans, and transition to an economy emitting small amounts of greenhouse gases while removing whatever we put up. I believe we’ll reach that goal eventually.

The question is: when?

In the meantime, I’ve grown increasingly concerned about Earth system tipping points. I wrote about this in Break Glass, Cool Planet, then attended the Global Tipping Points Conference in Exeter last summer. The reality is stark: the most terrifying outcomes could cross the point of no return in the next two to ten decades.

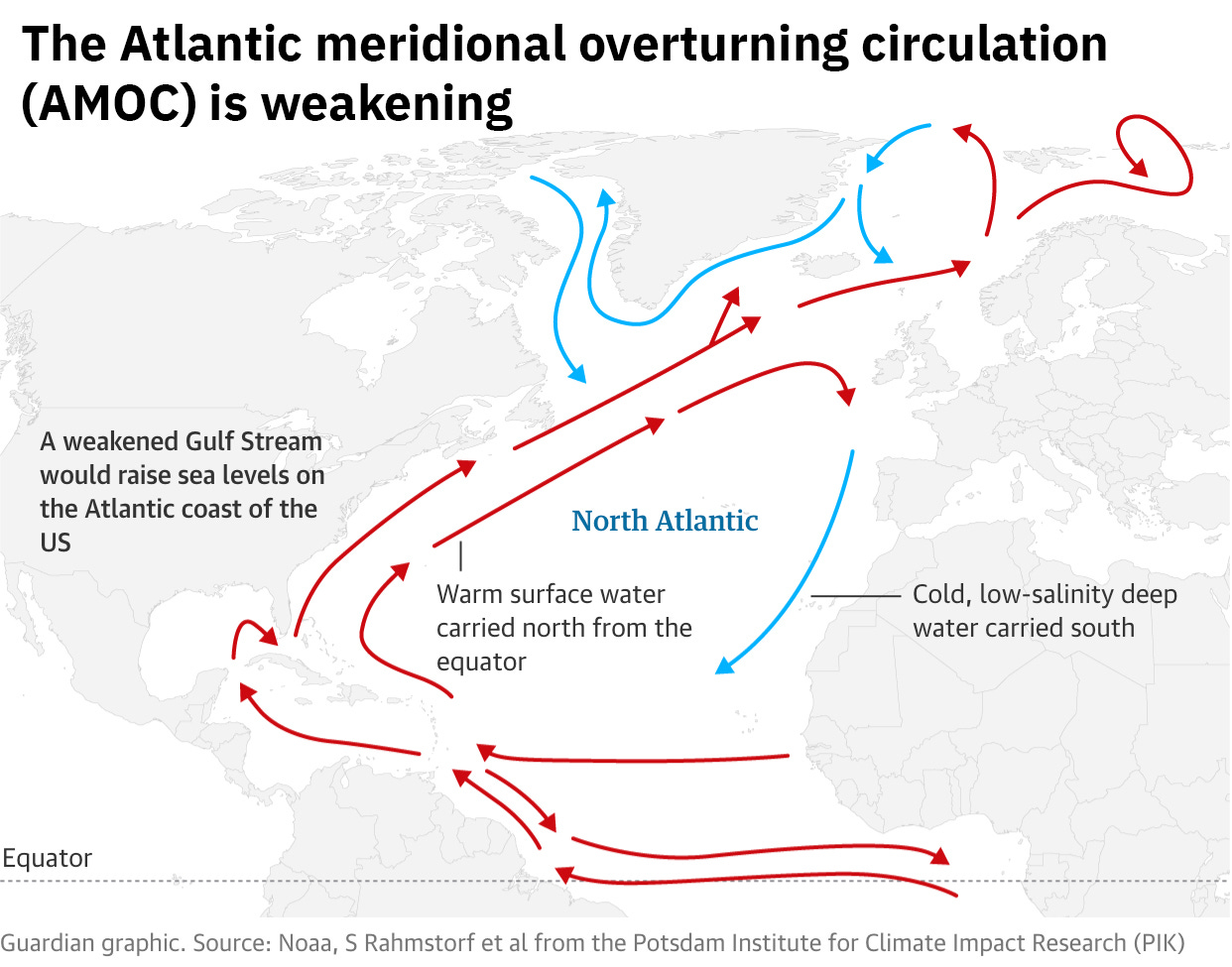

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) could collapse, plunging Europe into conditions that make agriculture impossible. No food means starvation and societal collapse.

Antarctic ice sheets are held in place by ice shelves that are being undermined from below by warm ocean water. If those systems tip into runaway feedback loops—and by “tip” I mean become unstoppable regardless of our future actions—we’re looking at multiple meters of sea level rise this century. Millions displaced. Entire island nations uninhabitable.

These are real, genuine threats. Most people on Earth don’t even know about them.

What’s worse: our models keep getting scarier. Events we thought would happen at 2°C or 3°C now show signs of occurring at lower temperatures. We’re essentially already at 1.5°C and in the realm of overshoot. Stefan Rahmstorf, co-author of a new paper on AMOC collapse risk, puts it bluntly:

“These numbers are not very certain, but we are talking about a matter of risk assessment where even a 10% chance of an AMOC collapse would be far too high. We found that the tipping point where the shutdown becomes inevitable is probably in the next 10 to 20 years or so. That is quite a shocking finding as well and why we have to act really fast in cutting down emissions.”

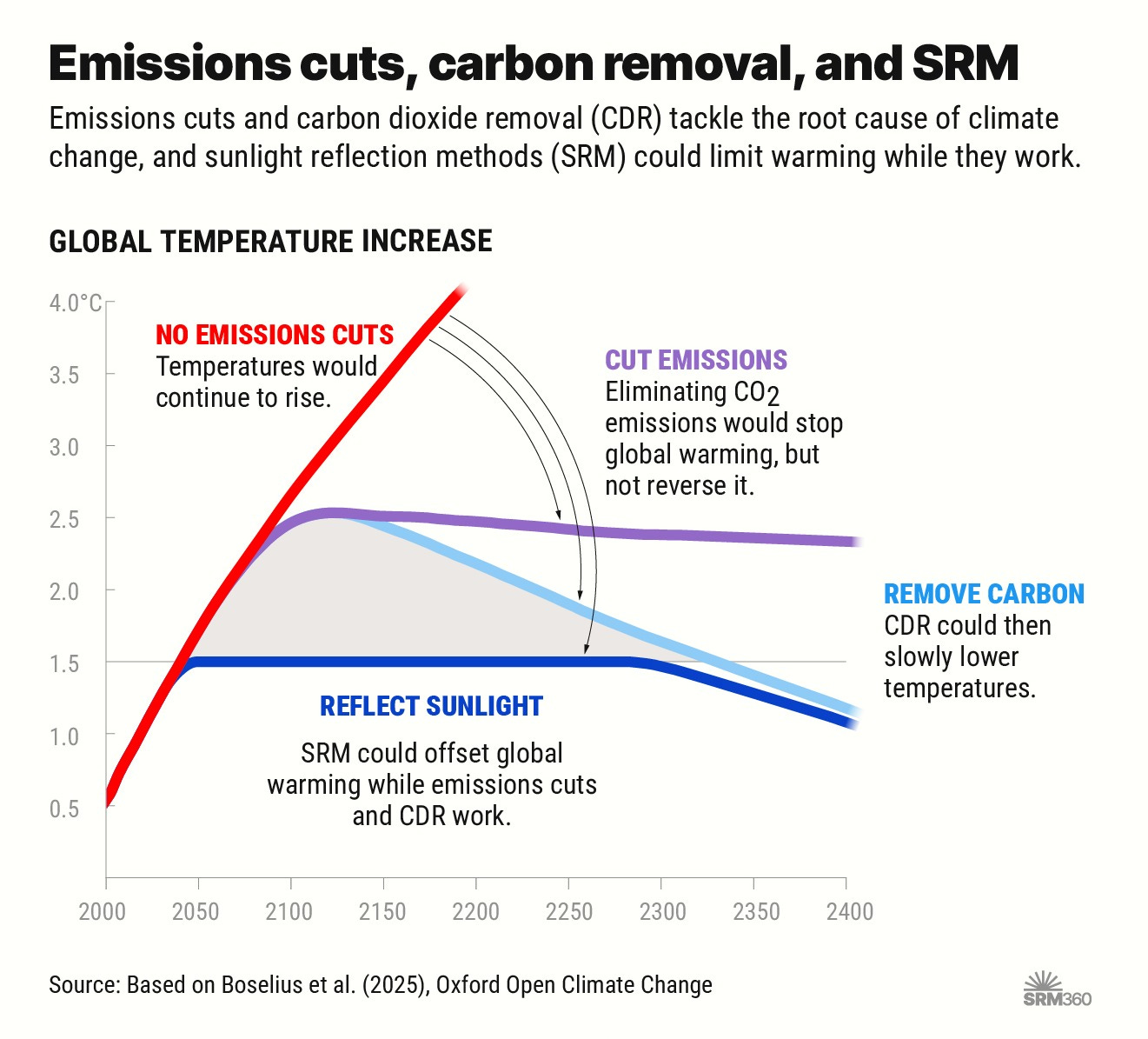

We cannot allow these tipping points to transpire. The consequences are too catastrophic, and we’re running out of time. But it’s not as simple as just relying on decreasing emissions and removing carbon dioxide. Even if we achieved net zero tomorrow, the planet would remain dangerously overheated for decades.

It is not possible to de-risk these tipping points through carbon management alone.

That logic drove me to investigate cooling interventions—technologies that could reduce tipping point risks and buy time while emissions cuts and carbon removal catch up. Also known as sunlight reflection methods (SRM) or solar geoengineering, these approaches could stabilize temperatures in the near term.

I’ll be honest: I’m not an expert in this field like I am in carbon removal. But over the past months, I’ve thrown myself into learning everything I could—reading books, listening to interviews, attending conferences, meeting with leaders in the field. The learning curve has been steep, and there’s no clear entry point for professionals who want to understand these options.

That’s why I created this guide. These are the resources helping me understand not just the science, but the politics, ethics, and practical realities of cooling interventions. SRM360 has excellent introductory materials (I recommend starting there), but if you want to grasp the complexities and tensions in this space, you need to go deeper.

Whether you have three hours or three weeks, this guide will help you understand what might be our most controversial—and necessary—climate tool. I’ll keep updating it as I learn more. And hit subscribe below to follow as I continue writing and advocating for cooling interventions.

II. What You Need to Understand Before Diving In

Before you start working through books and podcasts, you need a mental framework for how to think about cooling interventions. This isn’t just another climate technology to evaluate—it’s a fundamentally different kind of decision that cuts across science, politics, ethics, and justice in ways that carbon removal or emissions reduction don’t.

The Three-Tool Framework (And Why We Need All Three)

I used to think about climate solutions in two categories: reducing emissions and removing carbon. That seemed comprehensive. Cut what we’re putting up, clean up what’s already there, done.

But that framework is incomplete. Even if we achieved net-zero emissions tomorrow, the planet would remain dangerously warm for decades because of the CO₂ already in the atmosphere. Temperature doesn’t drop the moment emissions stop—it plateaus. And while temperatures stay elevated, we’re playing Russian roulette with tipping points.

So we actually have three tools:

Emissions reduction - Stop making the problem worse

Carbon removal - Address the root cause by drawing down atmospheric CO₂

Cooling interventions - Reduce temperature and tipping point risks in the near term

These aren’t alternatives. We need all three. Reduce, remove, and reflect. Emissions cuts and carbon removal remain essential because they’re the only paths to long-term stability. But they work on timescales measured in decades and centuries, and some tipping points might not wait that long. Cooling the planet by reflecting sunlight could buy time while the other tools catch up.

The critical thing to understand: cooling doesn’t solve climate change. It manages symptoms while we treat the underlying disease. Anyone telling you it’s a replacement for decarbonization is either confused or selling something.

The Core Tensions Everyone’s Grappling With

If you’re going to engage with this topic meaningfully, you need to understand that nobody has easy answers. The smart people working in this field are wrestling with genuine tensions that don’t resolve neatly:

Speed vs. uncertainty. Stratospheric aerosol injection could potentially cool the planet within months or years. That’s the appeal, as it’s the only lever we have that works on the timescale of tipping point risks. But we’re still not certain it would work as intended. We don’t fully understand regional impacts, precipitation changes, or long-tail risks. There are strategic questions we need to answer before deciding this is going to happen. So: Do we prioritize speed when the alternative might be catastrophic tipping points? Or do we prioritize certainty when getting more certain takes decades we might not have?

Research vs. deployment. Where’s the line between “learning about this” and “doing this”? Small-scale outdoor experiments are necessary to understand real-world behavior, but they make people understandably nervous. At what point does research become deployment? Who decides?

This is how most people in the field frame the tension. But I think there’s a different way to look at it: Research is clearly necessary—there are strategic questions we must answer. But I think deployment is inevitable. Someone is going to do this at some point, whether through coordinated governance or unilaterally. If that’s true, then the real question becomes: what actions do we take now to move from a potentially bad outcome (rogue actors, poor governance, unmitigated risks) to a much better outcome (multilateral coordination, thoughtful governance, careful risk management)? I don’t want a scenario where a single country enacts this without considering broader impacts. I want coordinated, multinational approaches that actively work to mitigate risks. That requires planning for deployment, not just debating whether it should happen.

Justice vs. urgency. Meaningful Global South participation in governance takes time—building capacity, ensuring their scientists inform their policymakers, creating legitimate decision-making processes. But climate impacts aren’t waiting. How do we go slowly enough to do this right, but quickly enough to matter?

Moral hazard vs. moral imperative. Does researching cooling interventions reduce pressure to cut emissions? Maybe. But refusing to research our only fast-acting temperature tool while tipping points approach? That is, in my opinion, a moral failure. This tension doesn’t fully resolve, but the imperative side weighs increasingly heavy.

Key Things to Know About the Debate

The positions aren’t symmetric. You’ll find plenty of climate scientists and activists who flatly oppose SRM—they think the risks are too high, full stop. The pro side is more complicated. Few people are out there unequivocally saying “we should definitely do this” (though I’m personally moving in that direction). Most supporters say “we should research this carefully” while hedging on deployment. Understanding this asymmetry helps you navigate the debate.

The taboo is real and has multiple sources. Many climate scientists and activists are deeply uncomfortable even discussing cooling interventions. Some of that discomfort is well-founded: the moral hazard concern is legitimate, the justice issues are real, the potential for bad governance is scary. There are also genuine scientific uncertainties—we don’t know for sure what happens when we significantly alter atmospheric chemistry, and there are real risks to weather systems and regional impacts. But here’s the catch: the taboo itself prevents us from doing the experimentation needed to answer those questions. Some of the discomfort is less rational—a sense that even talking about this is admitting defeat on emissions cuts. Understanding all these sources of discomfort helps you engage more productively.

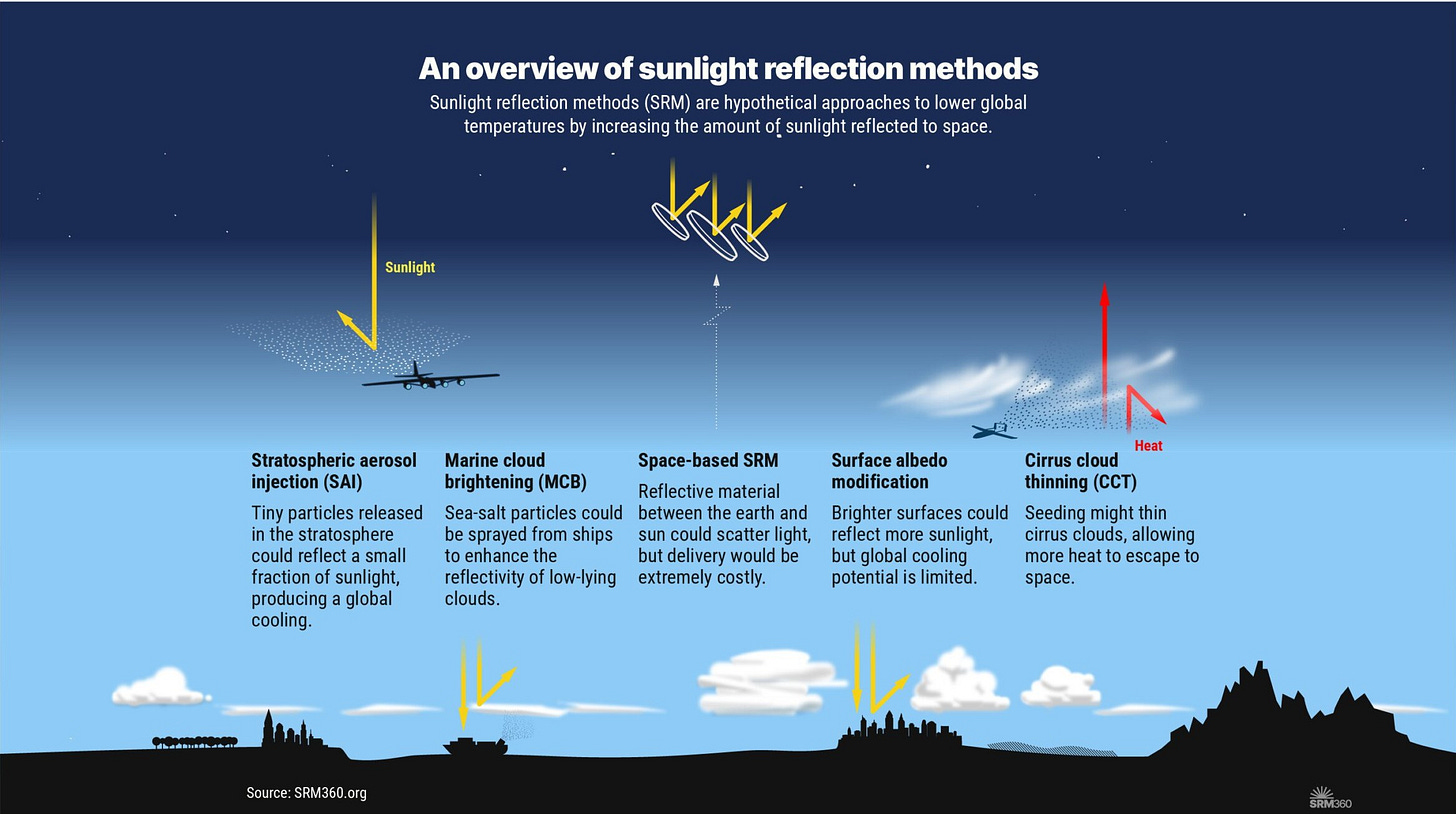

Different interventions have vastly different profiles. “Geoengineering” or “SRM” aren’t monolithic. Stratospheric aerosol injection, marine cloud brightening, and cirrus cloud thinning work through different mechanisms and carry different risks and uncertainties. Don’t lump them all together. Almost everyone talking about SRM focuses on SAI, but that’s not the only method. Some approaches might be more local or regional, less risky, or more palatable from a governance perspective. And there are other climate interventions beyond just cooling—like ice sheet preservation—that deserve consideration too.

Conspiracy theories vs. legitimate concerns. You’ll encounter both. Legitimate concerns sound like: “Who governs this? What about regional precipitation impacts? Doesn’t this create moral hazard?” Conspiracy theories sound like: “Chemtrails are already dimming the sun! Bill Gates is controlling the weather!” Learning to distinguish between thoughtful skepticism and paranoid nonsense matters.

What Informed Engagement Looks Like

After working through this guide, you won’t be a climate scientist or a governance expert. That’s fine. You don’t need to be. Here’s what informed engagement actually means:

You understand the lay of the land. You know why some people think researching cooling interventions is necessary and why others think it’s dangerous. You can explain why smart, well-intentioned people disagree without dismissing either side.

You can distinguish technical claims from ethical ones. “SAI would cool the planet approximately X degrees” is a technical claim. “We shouldn’t cool the planet without Global South consent” is an ethical claim. Both might be true, but they’re different kinds of statements requiring different kinds of evidence.

You recognize legitimate concerns vs. conspiracy theories. Not all skepticism is equal. Someone worried about governance is raising valid questions. Someone claiming chemtrails are already happening is not engaged with reality.

You ask good questions rather than claiming all the answers. The people doing this work are wrestling with genuinely hard problems. Informed engagement means understanding what questions matter and why they’re difficult, not pretending you’ve solved what experts haven’t.

If you can do those things, you’re informed enough to contribute to the conversation. That’s the goal here.

A note on acronyms: This field loves its initialisms. If you find yourself getting lost in alphabet soup (SRM, SAI, MCB, CCT, etc.), scroll down to the glossary at the end for a decoder.

III. If You Only Have 2 Hours

Maybe you don’t have time for a full deep dive right now. Maybe you just need enough context to not be lost when this topic comes up. Here’s the bare minimum to engage meaningfully:

Read: Gwynne Dyer’s op-ed “How can geoengineering help save us from the climate emergency?” (15-20 minutes)

This is the piece that introduced me to Dyer’s book Intervention Earth, which ended up being the single most useful resource I found on this topic. Dyer lays out the three-tool framework clearly and makes the case for why we need to overcome the taboo around discussing cooling interventions. It’s compelling without being alarmist, and it establishes the urgency around tipping points that makes this whole conversation necessary.

Watch: Wake Smith - “Geoengineering is Coming” (60 minutes)

This recent lecture is the best one-hour technical overview I’ve found. Smith makes a compelling case for why carbon management alone won’t solve the heating problem, with clear charts showing emissions growth, how we’re not on track with IPCC or Paris targets, and why we’re not sure if we’ve even reached peak emissions yet. He covers in depth how stratospheric aerosol injection works and mentions other methods like marine cloud brightening. If you’re going to spend one hour on this topic, watch this.

Skim: SRM360’s SRM Guides (30 minutes)

Work through the basics on their site: what SRM is, how the main techniques work (stratospheric aerosol injection, marine cloud brightening, cirrus cloud thinning), and what current research shows. This grounds you in the actual mechanisms rather than abstractions.

Total time: About 2 hours. You won’t be an expert, but you’ll understand enough to follow conversations and ask good questions.

If you have more time, move on to Section IV for the full learning sequence.

IV. The Full Learning Sequence

This is the path I took to understand cooling interventions. It’s not the only way, but it builds understanding logically with each phase giving you context for the next.

Phase 1: The Big Picture

Start with Intervention Earth by Gwynne Dyer. This is where I started and it’s still the best comprehensive overview. Dyer covers emissions reduction, carbon removal, and cooling methods as an integrated toolkit. You’ll understand why we need all three tools and why cooling isn’t a replacement for decarbonization or carbon removal. He walks through the causal chain (emissions → warming → tipping points), explains why both emissions cuts and carbon removal are moving too slowly, then surveys cooling methods with real nuance. It’s accessible without being simplistic, and it grounds everything in the urgency of tipping point risks.

Then add The Planet Remade by Oliver Morton for historical depth and philosophical context. Morton shows how humanity has been deliberately shaping Earth systems for centuries—from the nitrogen cycle to energy systems—which reframes geoengineering not as a wild departure but as a continuation of deliberate planetary influence, just with (hopefully) better intent and institutions. Written about a decade ago, it references older events but provides valuable context on how scientists and policymakers have thought about climate intervention over time. The framing helps you understand why this isn’t just sci-fi speculation. It’s a serious field with a real research history.

Optional: Listen to “We shouldn’t even be talking about geoengineering” - Oliver Morton on Saving the World from Bad Ideas (60 minutes). This conversation between Morton and host Mark Lynas captures the philosophical and emotional dimensions of the debate. Morton explains why not talking about SRM might itself be dangerous, especially as climate impacts accelerate. He’s thoughtful about the risks and honest about the uncertainties. Good complement to the books if you want the conversational format.

Why this order: Intervention Earth gives you the current landscape and the urgency. The Planet Remade gives you the intellectual history and helps you think about these tools in the broader context of how humans relate to planetary systems.

Phase 2: Understanding the Science & Tech

You don’t need to become a climate scientist, but you do need to understand the basic mechanisms of how these cooling interventions actually work, what the models show, and—critically—what we don’t know.

Start with the SRM360 website overview materials. If you did the 2-hour version in Section III, you’ve already covered this. If not, their site is designed as a straightforward explainer for smart non-experts. Work through these in order:

The “Why SRM?“ overview page

Individual technique explainers (stratospheric aerosol injection, marine cloud brightening, cirrus cloud thinning)

The “Could SRM help?” section to understand why this is useful

This gives you the technical grounding without overwhelming you with academic papers. You’ll understand what’s being proposed, how it mimics natural processes (like volcanic eruptions), and what the current research shows about potential impacts.

Read the 2023 White House Report on SRM. This is a comprehensive scientific assessment from the previous administration. It’s a long read but goes deep into what we know, what we don’t know, and what research priorities exist. Essential if you want to understand the state of the science beyond introductory overviews.

Optional: Play with the Reflective SAI Simulator. Fair warning, this tool is designed more for policymakers and researchers war-gaming deployment scenarios than for people learning the basics. It’s not essential, but if you want to visualize what different deployment approaches might look like in practice, it’s there.

Why this phase matters: You can’t meaningfully engage with governance or justice questions if you don’t understand what’s being governed. The science isn’t that complicated once someone explains it clearly. SRM360 does that job well.

Phase 3: The Governance Challenge

Here’s where it gets messy. Even if cooling interventions are technically feasible, the questions of who decides, who’s accountable, and how we prevent unilateral action are extraordinarily difficult. This is arguably the hardest part of the whole discussion.

Read Five Times Faster by Simon Sharpe. This book isn’t about SRM, but it’s essential for understanding how climate policy actually gets made—and why it so often fails. Sharpe worked at COP negotiations and shows how the machinery of international climate governance works (or doesn’t). It’s pragmatic, sometimes frustrating, and gives you the context for why creating governance frameworks for cooling interventions is so complicated. You need to understand the system these decisions would happen within.

Watch the SRM360 webinar on bans and moratoria. This covers the current legislative landscape—what different proposals actually mean (non-use agreements vs moratoria vs bans), who’s pushing for what, and the implications of each approach. It’s practical and clarifying on a topic that often generates more heat than light.

Listen to the Cynthia Scharf episode of “Saving the World from Bad Ideas.” Scharf is a former UN climate advisor who explains why the taboo around discussing SRM might pose greater risks than researching it, especially as temperatures surge and impacts escalate. The conversation covers the governance void we urgently need to address.

Optional: Children of a Modest Star by Jonathan Blake & Nils Gilman. This book argues that nation-states are a relatively new social technology and that planetary-scale problems like climate change require new forms of planetary governance. It’s philosophically grounding but less immediately practical than Five Times Faster. If you want the theoretical framework, read the book. If you want just the thesis, listen to the Climate Reflections podcast episode interviewing the authors. You’ll get the key ideas in an hour.

Why this order: You need to understand how climate policy actually works (Sharpe) before you can evaluate what governance structures might work for SRM. Then the webinar grounds you in current debates, and the Scharf conversation adds the urgency dimension.

Phase 4: Justice and Ethics

The technical and governance questions are hard. The justice and ethics questions might be even harder—and they’re the ones that matter most for whether any of this should ever be done.

Why justice is central here, not peripheral: The Global South faces the most severe impacts from climate change—they’re living with consequences they did least to cause. Any intervention that affects the entire planet requires their meaningful participation, not just consultation. This isn’t about being nice or inclusive for its own sake. It’s about recognizing that decisions affecting everyone must include everyone, especially those with the most at stake.

Start with After Geoengineering by Holly Jean Buck. This is the essential justice-centered treatment of climate interventions. Buck explores what it would mean to live in a world where we’re using these technologies - who controls them, who benefits, who bears risks, and how to prevent corporate capture or colonial dynamics. She explicitly argues that if we ever use these tools, they must serve a democratic, fossil-free restoration project, not prolong fossil fuel use. The book blends field reporting with speculative fiction to make the tradeoffs tangible. It’s the most thoughtful treatment I’ve found of how to think about climate interventions from a justice-first perspective.

Explore the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering (DSG) resources. Start with their writing and commentary section, particularly pieces like their article on legitimacy that frames the challenge as “going slowly as quickly as possible.” They also maintain a library of learning resources focused on justice dimensions of SRM. DSG is doing work ensuring that Global South voices and perspectives are centered in SRM research and governance discussions—not as an afterthought, but as foundational.

Check out the Degrees Initiative. Their core thesis is crucial: if Global South policymakers are going to make well-reasoned decisions about climate interventions, they need to be informed by their own scientists and researchers, not just by research coming out of wealthy Western institutions. Degrees works to build that research capacity and ensure that knowledge production about SRM isn’t controlled by a handful of countries. This matters because perspectives, priorities, and risk assessments differ—and they should inform the global conversation.

Why this comes last: You needed to understand what’s being proposed (Phase 2) and how governance might work (Phase 3) before you can meaningfully engage with the ethical critiques. The justice questions aren’t separate from the technical and political ones—they’re woven throughout. But Buck and these organizations make them central rather than peripheral, which is where they belong.

V. Additional Resources by Topic

Once you’ve worked through the main learning sequence, you might want to go deeper in specific areas. Here’s where to go next, organized by interest:

For Deeper Science and Modeling

Sam Kaufmann’s SRM Paper Repository - This is a meticulously curated spreadsheet of hundreds of published papers on SRM modeling, with useful metadata. If you want to dive into the academic literature, this is your starting point. Sam Kaufmann, an analyst at SilverLining, has done the work of organizing the field’s research output.

Reflective SAI Simulator - More useful once you understand the basics. Lets you visualize different deployment scenarios as they’re being developed by modelers. Designed for policymakers and researchers but accessible if you’ve done the foundational learning.

Climate Reflections Podcast - The full series from SRM360 goes deep on technical topics with leading researchers. Good for when you want scientist-to-scientist level detail explained accessibly.

For Governance Deep Dives

White House Report on SRM - The 2023 “Congressionally-Mandated Report on Solar Radiation Modification” provides the U.S. government’s assessment of knowledge gaps and research priorities (as they existed in the previous administration). Essential for understanding the policy landscape, particularly U.S.-focused impacts and considerations.

SRM360 Governance Resources - Their site includes ongoing coverage of legislative developments, governance proposals, and policy debates. Start with their webinars for accessible overviews of current issues.

For Justice Perspectives

DSG Library - The Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering’s learning resources focuses specifically on justice dimensions and Global South perspectives.

Degrees Initiative country materials - Their website includes regionally specific materials and perspectives. Worth exploring to understand how different parts of the world are engaging with these questions.

Research Trackers and Tools

SRM360 Trackers:

Outdoor Research Tracker - Monitors actual outdoor experiments and research activities

Funding Overview - Tracks where money is flowing in the field

Both help you understand what’s actually happening beyond the theoretical discussions.

Key Research Institutions

If you want to follow the research directly:

University of Chicago Climate Systems Engineering Initiative - Leading U.S. research hub

Harvard Solar Geoengineering Research Program - One of the oldest and most established programs

University of Washington Marine Cloud Brightening Program - Focused specifically on MCB research

These sites include papers, seminars, and research updates if you want to track cutting-edge work.

VI. Staying Current

This field moves fast. New research, policy developments, and governance debates emerge constantly. Here’s how to keep up:

Essential Newsletters

Solar Geoengineering Updates by Andrew Lockley is the single best roundup of everything happening in this space. He pulls together published papers, news articles, policy developments, and basically anything else relevant. It’s comprehensive without being overwhelming, and it’s how I stay informed. Subscribe to this.

The ARC: Thoughts on a safe climate future by Joshua Elliott and the ARC team has also been great lately, and I covered why in my last piece about the Climate Emergencies Forum. I hope they continue to publish more soon.

Twitter/X Accounts to Follow

I maintain a curated Twitter list of key accounts covering SRM and climate interventions. Rather than list them all individually here, follow the list and you’ll get the most important voices and updates.

Two accounts worth calling out specifically:

@geoengineering1 - Andrew Lockley’s account, the same person behind the newsletter. Best single source for comprehensive coverage.

@Climate_of_apes - A webcomic artist who really understands the nuances of the field and presents them accessibly. More fun than you’d expect from climate policy content.

Organizations Working in This Space

Note: I’m updating this list as I learn about more organizations. Last updated October 2025. If you know of others doing important work, let me know in the comments.

Research and coordination:

SRM360 - Knowledge hub and information clearinghouse. Their site is where you go for clear, accessible explanations.

Reflective - Research organization that helps set the agenda for what areas of SRM research need the most attention.

Degrees Initiative - Building Global South research capacity and engagement.

SilverLining - Research and policy organization working on climate intervention science.

Planetary Sunshade Foundation - Organization focused on space-based SRM research and advocacy.

Governance and deliberation:

Centre for Future Generations (CFG) - Advising European institutions on governance frameworks for climate interventions.

Climate Hub - Focused on briefing and working with policymakers and institutions to ensure that key decision makers are well informed on intervention options.

Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering (DSG) - Focused on inclusive, justice-oriented governance processes.

Healthy Planet Action Coalition (HPAC) - Advocacy organization working on high-level diplomacy with nation states to develop integrated climate action plans combining reduction, removal, and reflection.

Chesapeake Climate Action Network - Traditional environmental activist organization that has recently begun engaging with geoengineering at the policy level.

Arctic-focused:

Operaatio Arktis - Finnish youth organization focused on preservation of the Arctic and avoiding tipping points.

The Arctic Climate Emergency Response (ACER) Initiative - An initiative spun out of ARC that focuses on research and experimentation in cloud thinning to protect Arctic ice.

Private sector:

Make Sunsets - Controversial company doing small-scale SAI releases. Their approach raises serious governance questions for many people.

Stardust - Another private company exploring SRM. Not much is currently known about their business.

Research funding:

ARIA - UK’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency, funding various aspects of cooling research within their “Exploring Climate Cooling” program.

ARC (Renaissance Philanthropy) - Philanthropic initiative supporting climate intervention research and capacity building.

Outlier Projects - Frontier research funding for prevention of catastrophic climate risks.

The Navigation Fund - Research funding to navigate and prevent climate risks resulting from temperature overshoot.

These organizations have different approaches, priorities, and levels of controversy. Following them helps you understand the breadth of perspectives in the field.

VII. Common Questions and Pushback

If you start talking about cooling interventions, you’ll encounter pushback. Some of it is thoughtful and legitimate. Some of it is knee-jerk and ideological. Here’s how I think about the most common concerns:

“Doesn’t this let fossil fuel companies off the hook?”

This is the moral hazard argument, and it’s legitimate. If people think we have a technological fix for warming, does that reduce pressure to cut emissions?

My take: This concern would be more compelling if emissions cuts were actually happening at the necessary pace. They’re not. We’re decades behind where we need to be, and the political will for rapid decarbonization remains weak in most countries. The idea that discussing cooling interventions will somehow make emissions cuts slower assumes they’re currently fast enough to matter. They’re not.

That said, the concern isn’t baseless. Fossil fuel interests absolutely would use this as cover if we let them. That’s why it’s critical that any research or governance in this space explicitly ties cooling interventions to aggressive decarbonization, not as an alternative to it. Holly Jean Buck makes this point forcefully in After Geoengineering. These tools must serve a fossil-free transition, period.

Where to learn more: Buck’s book. Also the DSG materials on ensuring cooling interventions don’t become a substitute for mitigation.

“Isn’t this just rich countries imposing risk on the Global South?”

Yes, potentially. And that’s exactly why justice and governance are central to this conversation, not peripheral.

My take: The Global South already bears disproportionate climate risks from emissions they barely contributed to. Any intervention that affects the entire planet requires their meaningful participation. Not consultation after decisions are made, but actual shared decision-making power. This isn’t about being nice. It’s about recognizing that decisions affecting everyone must include everyone, especially those with the most at stake.

The risk here is real: wealthy countries could research, develop, and potentially deploy cooling interventions that serve their interests while imposing different (or greater) risks on others. Preventing that requires building governance structures and research capacity now, before deployment becomes a possibility. That’s what organizations like Degrees Initiative and DSG are working on.

Where to learn more: Phase 4 of the learning sequence. Start with Buck, then explore DSG and Degrees Initiative materials.

“What if someone just does this unilaterally?”

The “rogue actor” scenario keeps people up at night. What if a country or even a wealthy individual decides to start injecting aerosols without international consent?

My take: This is a governance problem, not a technical problem. And it’s precisely why we need to build governance frameworks now, before crisis conditions make unilateral action more tempting. The worst time to figure out rules is when someone’s already breaking them.

The uncomfortable truth is that stratospheric aerosol injection is relatively cheap and technically simple. A mid-sized country could afford it. A sufficiently motivated super-billionaire could afford it (though maybe not have the airbase access). The barriers aren’t technical or financial—they’re political and normative. We need strong international norms and potentially treaties establishing that unilateral deployment is unacceptable. But building those takes time and requires open discussion of what we’re trying to prevent.

Refusing to talk about SRM doesn’t make the rogue actor problem go away. If anything, it makes it worse by ensuring we have no frameworks in place when someone decides to act.

Where to learn more: Five Times Faster on governance challenges. The SRM360 webinar on bans and moratoria. Cynthia Scharf’s podcast episode.

“Won’t this reduce urgency on emissions cuts?”

The mitigation deterrence concern: if we have a plan B, won’t we slack on plan A?

My take: Show me evidence that climate urgency is currently high enough that it could be reduced. Where are these aggressive emissions cuts that might slow down if we research cooling? Where is this political will that might evaporate?

The reality is that most countries are missing their Paris targets by huge margins, and the targets they set weren’t stringent enough anyway. The U.S. elected an administration that is actively discrediting climate research, defunding programs that support decarbonization and carbon removal, and taking a no-holds-barred approach to fighting against climate action. The idea that discussing cooling interventions will somehow reduce already-insufficient climate action doesn’t match what I see happening in the world.

What does worry me: if we reach a point where cooling interventions are deployed, they could create complacency. “We’ve solved warming, why bother with the hard work of decarbonization?” That’s a real risk. Which is why any deployment must be explicitly tied to continued emissions reductions and carbon removal scale-up, not positioned as a replacement for them.

Where to learn more: Buck on how to ensure interventions serve decarbonization rather than replacing it. Morton on why not discussing this creates its own risks.

“What about termination shock?”

Termination shock is the rapid warming that would occur if stratospheric aerosol injection were suddenly stopped after sustained deployment. Because SAI masks warming rather than addressing the root cause, stopping it abruptly would unleash accumulated heat. Temperatures would revert to where they would have been based on greenhouse gas concentrations, and this risk compounds over time.

My take: This is a real risk, but it doesn’t concern me as much as some other potential issues. Here’s why:

First, the physics: if deployment stopped, warming wouldn’t be instantaneous. The aerosols remain in the stratosphere for about one to two years. That provides a window—not a long one, but real time—for redeployment. If one nation-state were managing this and something went wrong (political collapse, funding failure, whatever), others could step in before the cooling effect fully dissipated. It’s not a light-switch situation.

Second, the awareness of termination shock risk could actually be a forcing function. If the world knows that stopping SAI means rapid warming, that creates strong incentive to maintain aggressive emissions reductions and carbon removal scale-up. You can’t just cool the planet and forget about the underlying problem. The existence of this risk might reinforce the urgency of addressing root causes rather than undermining it.

Third—and this is critical—SAI does nothing about ocean acidification. As we continue emitting greenhouse gases, oceans keep absorbing CO₂ and becoming more acidic. This threatens fisheries, coral reefs, and the millions of people whose livelihoods depend on healthy ocean ecosystems. That’s going to get worse regardless of whether we’re cooling the atmosphere. This makes crystal clear that cooling is not the solution—it’s a temporary measure to buy time while we do the actual work of decarbonization and carbon removal.

So yes, termination shock is real. But it’s a risk of deployment, not research. And it’s specifically a risk of deployment without simultaneous action on emissions and carbon removal—which is exactly the scenario we need to prevent through governance.

Where to learn more: The White House SRM report discusses termination shock. Morton’s The Planet Remade covers it in the context of deployment risks.

A Note on Conspiracy Theories

You’ll also encounter people who think chemtrails are already happening, that Bill Gates is secretly controlling the weather, or that geoengineering is a plot to depopulate the planet.

These aren’t legitimate concerns. They’re conspiracy theories detached from reality. Don’t waste time engaging with them as if they’re equivalent to the thoughtful critiques above. The difference between “I’m worried about governance” and “they’re already spraying us” is the difference between a policy debate and paranoia.

Learning to distinguish between the two matters. The concerns in this section are legitimate and deserve serious engagement. Chemtrail theories don’t.

VIII. Glossary & Quick Reference

Key Terms and Acronyms

Albedo - The fraction of solar radiation reflected by a surface. Higher albedo means more sunlight reflected. Cooling interventions work by increasing Earth’s overall albedo.

AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation) - Major ocean current system. Its collapse would have catastrophic impacts on European climate and global weather patterns.

CCT (Cirrus Cloud Thinning) - Deliberately thinning high-altitude cirrus clouds to allow more heat to escape to space. Less studied than SAI or MCB.

CDR (Carbon Dioxide Removal) - Technologies that remove CO₂ from the atmosphere. Distinct from cooling interventions - CDR addresses the root cause, cooling manages symptoms.

Climate Interventions - Broader term encompassing cooling methods and other large-scale interventions like ice sheet preservation. Emphasizes deliberate action to address climate change beyond emissions reduction.

MCB (Marine Cloud Brightening) - Spraying seawater particles into low-lying marine clouds to make them more reflective. Works by increasing cloud droplet concentration. There is active experimentation in Australia using this approach to potentially cool waters over coral reefs, demonstrating possible local or regional applications. MCB is harder to model than SAI, which is why it’s not as well studied.

Mitigation Deterrence - Specific form of moral hazard where the existence of cooling research/deployment reduces political will for emissions reductions.

Moral Hazard - The concern that having a technological backup plan (cooling) might reduce motivation for the necessary work (emissions cuts and carbon removal).

SAI (Stratospheric Aerosol Injection) - Injecting reflective aerosols (typically sulfur dioxide) into the stratosphere to scatter sunlight, mimicking the cooling effect of volcanic eruptions. The most-studied cooling intervention.

Solar Geoengineering - Another term for the same set of interventions. “Geoengineering” historically included both cooling methods and carbon removal, but the field has largely split these into separate discussions.

SRM (Sunlight Reflection Methods) - The current preferred term for technologies that reflect sunlight back to space to cool the planet. Originally stood for “Solar Radiation Management,” which was coined as a joke with a bureaucratic-sounding name so NASA officials wouldn’t notice an event about it. The field has moved away from “management” language toward “reflection methods.”

Termination Shock - The rapid warming that would occur if stratospheric aerosol injection were suddenly stopped after sustained deployment. A major risk factor for SAI.

Tipping Points - Thresholds in the climate system beyond which changes become self-reinforcing and potentially irreversible (e.g., AMOC collapse, ice sheet loss, permafrost methane release).