I Grew Up in Hot Weather

And Metaphorically, You Did Too

We left town for a weekend just as the temperature started to drop. Seattle doesn’t get very cold most winters, but this January, we had a week with overnight temperatures below freezing, and I’d left the garden hose attached to the outdoor spigot. The spigot cracked and leaked for hours before our landlord got there, and now we’re waiting to find out if there’s damage to the foundation.

It’s frustrating because unscrewing the hose would have taken thirty seconds. Of course, I knew intellectually that freezing water expands and can burst pipes. But I grew up in Arizona, where I learned a completely different set of survival skills: keep the shades drawn during the day, carry water everywhere, and for the love of god, never touch a seatbelt buckle that’s been baking in the sun. Those responses are automatic for me. But I have to consciously think about what do in cold weather, which means sometimes I don’t.

We Gain Expertise Through Experience

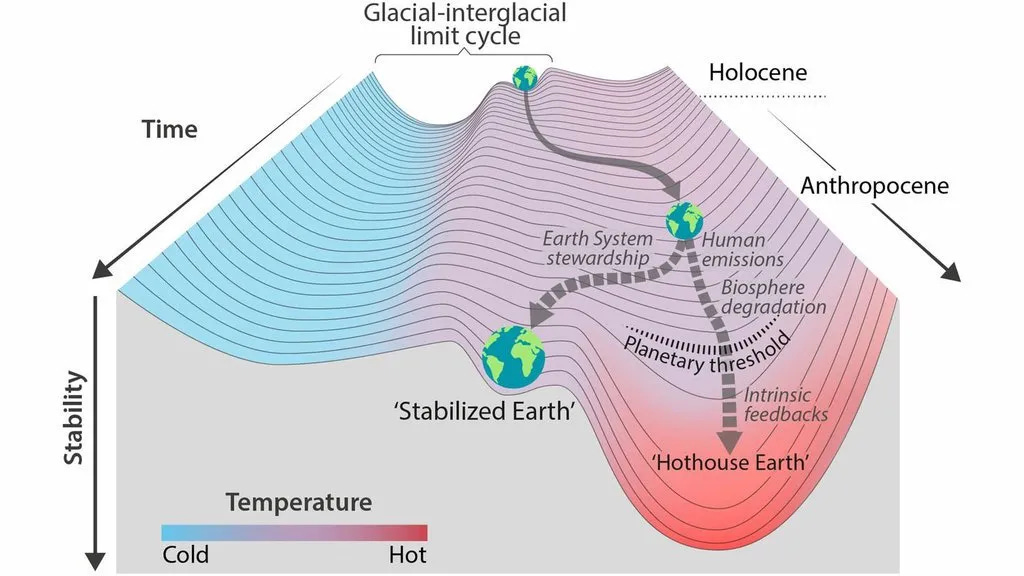

We’re all from warm weather, in a sense. Human civilization developed during an unusually stable stretch of Earth’s climate, the ten thousand years since the last ice age, and that stability was consistent enough for us to develop agriculture and build cities and establish trade routes that depend on predictable seasons and coastlines. Nobody alive has experiential pattern recognition for ice sheet collapse or permafrost methane release or the shutdown of the ocean circulation patterns that regulate temperatures across the Northern Hemisphere. We’ve never lived through these things. Neither did our parents, or theirs, going back hundreds of generations.

Human cognition evolved for a different set of problems. We’re good at threats we can see and have seen before: a rustle in the grass that might be a predator, or a facial expression that signals anger. Our threat-detection systems run on pattern-matching, and the patterns come from lived experience. But the difference between a million and a billion doesn’t register viscerally, even though one is a thousand times larger. Thirty years from now feels like an abstraction in a way that next week doesn’t. We usually expect causes and effects to be proportional, so the idea that a small temperature increase could trigger cascading failures feels wrong even when we understand the mechanism intellectually. And we’re particularly bad at risks we’ve never encountered, because there’s nothing to pattern-match.

The result is that you can know something without feeling it. Climate scientists who’ve spent decades studying ice sheet dynamics can explain exactly how Thwaites Glacier could destabilize and what it would mean for sea levels, and still not walk around with the gut-level urgency that the situation warrants. The knowledge sits in one part of the brain while the motivation (or openness) to act sits in another, and the connection between them depends on experiences we don’t have.

When the Frame Breaks

At Davos this year, not a single world leader mentioned climate change. The entire conversation, if mentioned at all, was about energy security. Marianne Hagen, a former Norwegian deputy minister of foreign affairs, watched this shift happen in real time after Russia launched its war on Ukraine. In a recent Atlantic article about geoengineering research on Antarctic glaciers, Hagen described her own transformation on the subject:

Marianne Hagen, a former Norwegian deputy minister of foreign affairs, told me that she’d long considered geoengineering “science fiction and just something not worth spending a lot of time on.” Then she watched as the Ukraine war changed the conversations around her: Energy security came to the forefront of European politics, and “nobody talked about energy transition anymore.” She thought of the vulnerable coastal nations she’d visited as a government official and, in 2024, signed on to co-lead the curtain project with Moore. “I ended up in John’s camp, mostly out of despair, because I could not see a safe pathway forward for future generations without doing the necessary research on these Band-Aid, buy-time solutions,” she said.

Her phrasing, “mostly out of despair,” stayed with me. She didn’t change her mind because she encountered new data or better arguments. She changed because her existing frame broke completely, and she had to construct a new one from the wreckage. The familiar way of thinking about the problem stopped working, and only then could she see what had been invisible before.

If Tipping Points Tip, It’s Already Too Late

Bill Gates has been one of the more visible funders of geoengineering research, including early support for Harvard’s SCoPEx stratospheric aerosol experiment. At a recent talk at Caltech, he was asked about when he’d support actually deploying these technologies, not just researching them. According to Axios, which reported on his comments, Gates said he’d support deployment if the planet hits climate tipping points. Axios added context, noting that scientists say such scenarios are “likely decades away, even as extreme weather worsens today.”

Gates understands the science better than most, yet he frames deployment as something you do after tipping points are reached. The reporting frames tipping points as something decades in the future that we’d approach gradually, like a budget running down. Both framings are exactly backwards, and they illustrate this cognitive problem with uncomfortable clarity.

Tipping points aren’t a line you approach gradually and can step back from. They’re phase transitions, points where a system shifts into a new state and can’t easily return. Picture leaning back in a chair on two legs. You can lean a little, lean a little more, it’s fine, it’s fine…and then suddenly it’s not fine, and you’re on the floor. The fall happens fast. There’s a threshold you cross where the dynamics change entirely, and you can’t just lean forward again to fix it.

The whole reason tipping points are dangerous is that they’re irreversible once crossed. Waiting until after a tipping point tips is like waiting until after your pipes burst to unscrew the hose. The intervention only works if it happens before.

Gates is one of the most analytically rigorous people on the planet, and he’s funded serious research in this space for years. But he’s reasoning about an unfamiliar risk using frameworks built for familiar ones, treating a non-linear threshold like a linear decline you can monitor and respond to proportionally. That’s not how these systems work.

The Axios framing compounds the error. “Decades away” suggests we have time to wait, as if the relevant question is when tipping points arrive rather than how long it takes to prepare for them. Cooling interventions can’t be deployed overnight. They require years of research to understand regional effects, international governance frameworks that don’t currently exist, diplomatic relationships that take time to build, and public trust that has to be established before a crisis rather than during one. If you start preparing after tipping points are triggered, you don’t have time to do any of this responsibly. You get improvisation under pressure, which is exactly the scenario everyone agrees we should avoid.

“Decades away” suggests we have time to wait, as if the relevant question is when tipping points arrive rather than how long it takes to prepare for them.

How To Compensate For Missing Intuition

When your cognitive architecture isn’t built for the risks you face, trying harder to care doesn’t help. Willpower doesn’t rewire pattern recognition. What works is building external systems that compensate for what the brain can’t do natively, and humans are actually quite good at this. We can’t intuitively calculate compound interest, so we built spreadsheets. We can’t perceive ionizing radiation, so we invented Geiger counters. The history of science is largely a history of building instruments that translate invisible phenomena into something we can perceive and act on.

For climate tipping points, this means building tools that make the abstract concrete. Not just temperature projections on a chart, but simulations that let you see what specific changes mean for specific places: what your city looks like with seven feet of sea level rise, or how agricultural zones shift when monsoon patterns change. The goal is to engage the parts of the brain that respond to visceral experience, not just the parts that process data.

It also means building institutional structures that force sustained attention. The problems that get solved in this world are the ones with budgets, reporting cycles, and constituencies that hold decision-makers accountable. Quarterly earnings get attention because there’s infrastructure that makes them visible and consequential every three months. Tipping point risks need equivalent infrastructure, not because corporate earnings and ice sheet stability are the same kind of thing, but because human organizations lose focus on anything that doesn’t have structural reinforcement.

And it means preparing the option space before you need it. We need research that develops the knowledge base, governance frameworks that establish how decisions would get made, diplomatic relationships that enable coordination, and trust-building with publics who will need to understand what’s happening and why. All of this takes years, and none of it can be rushed in a crisis.

What We Do Now

I’m going to remember to unscrew the hose next winter, not because I’ll suddenly have cold-weather instincts but because I’ve added it to my phone’s reminders app. I’ve built a small external system that compensates for the pattern recognition I lack and probably won’t develop at this point in my life.

That’s the work for tipping point risks, at a civilizational scale. We don’t have the intuitions for these dangers, and we’re not going to develop them through experience, because by the time we experience ice sheet collapse, it’s too late to prevent it. We have to build the systems that make these risks visible and actionable, and we have to build them before we need them.

We still have some time left. But time runs differently for preparation than for crisis. The moment when action becomes obviously necessary is long after the most effective action could have happened. Effective action requires groundwork laid years earlier, by people who could see what wasn’t yet visible to everyone else.

I didn’t grow up in cold weather, and none of us grew up with tipping points. The risks that will define this century aren’t ones our intuitions are equipped to handle. Recognizing that is where the work begins.

This and every other article I publish is free because I want these ideas to reach as many people as possible. Paid subscriptions are how I keep doing this work independently. They allow me to follow the research on climate interventions and meet the researchers, practitioners, founders, and policymakers shaping how this landscape evolves.

Paid members get access to our community chat, where we discuss the latest developments in climate interventions and make sense of them together. I’m sharing all the really interesting videos, papers, stories, and other links I’m coming across in there. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, I’d appreciate your support.

I wonder if VR/AR could be a helpful tool for helping people envision potential tipping point impacts in their communities?