The Positive Case For Global Cooling That Few Seem Willing to Make

The Temperature Stabilization Imperative

I spent a decade building carbon removal infrastructure, believing we could scale our way out of the climate crisis. The math proved me wrong. In a more perfect world, we would today be well on our way to removing 285 million tonnes of CO2 per year by 2030, but what we’ve achieved so far is barely a drop in the bucket.

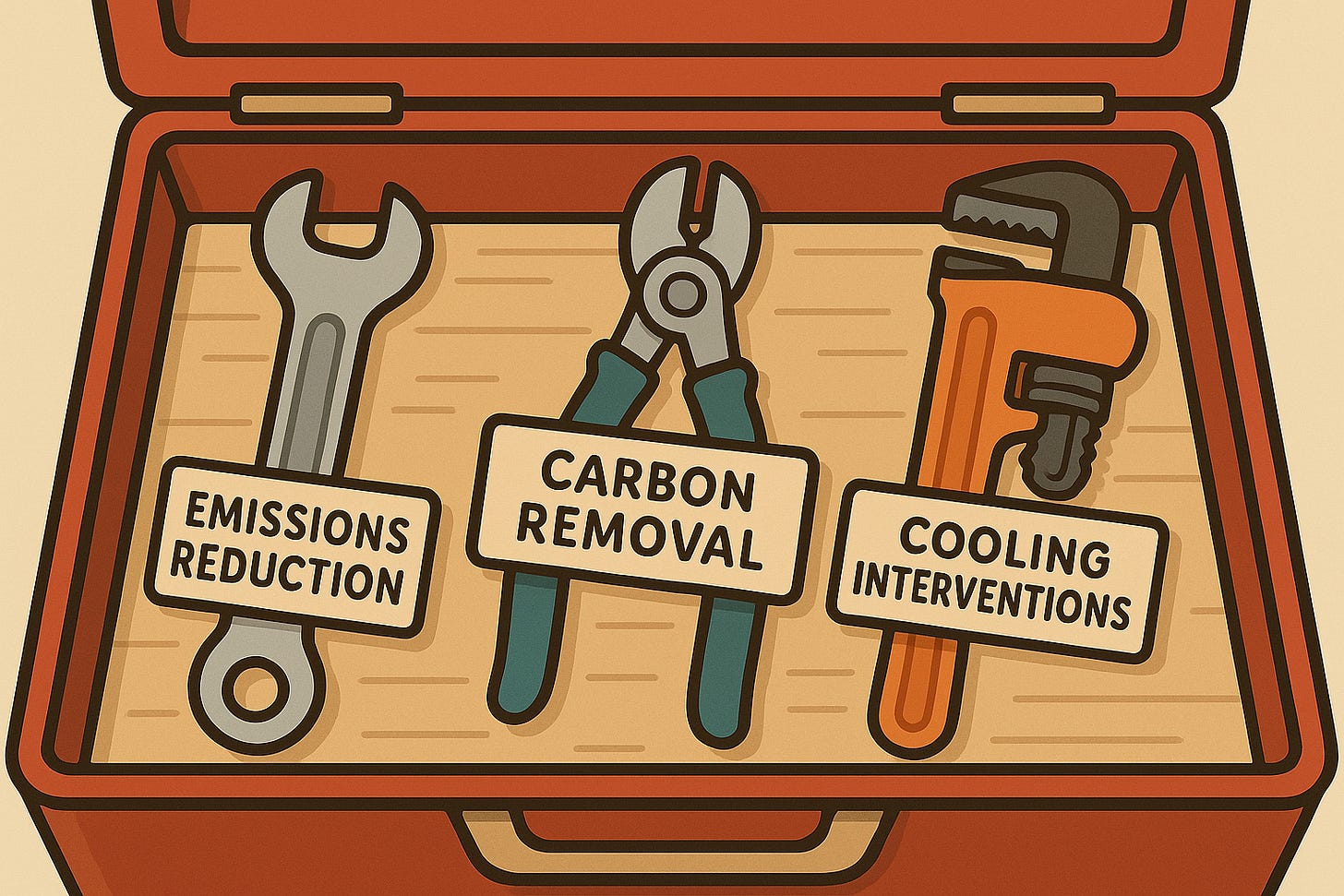

This forced me to step back and see the bigger picture. We have exactly three tools to prevent catastrophic warming: emissions reduction, carbon removal, and cooling interventions. Despite heroic efforts, emissions aren't falling fast enough. Carbon removal isn't scaling fast enough. That leaves cooling—which could stabilize temperatures while the other two catch up. Yet we've barely begun preparing this option. When I work backwards from our objective—safe atmospheric CO2 levels and limited warming—the evidence points strongly toward needing all three.

I've come to an uncomfortable but logical conclusion: temperature stabilization through cooling interventions will be required. Not as a replacement for emissions cuts or carbon removal, but to buy them time to succeed. Cooling is going to be needed, and what we must do now is evaluate which methods we'll use and how we'll govern them responsibly.

Mapping the Current Ecosystem

Over the past months, I've been exploring the global cooling landscape. What I found was both encouraging and concerning.

The encouraging part: excellent organizations are doing vital work. ARIA is pushing research boundaries with serious government backing. SRM360 translates complex science and ecosystem data into resources journalists and policymakers can actually use. Reflective builds tools that help researchers coordinate and share findings. The Degrees Initiative ensures Global South voices are included from the start. Even Make Sunsets, controversial as they are, demonstrates what happens when someone decides to just start.

Beyond these NGOs and startup, research labs and think tanks are advancing the science. Universities are running climate models. Policy centers are exploring governance frameworks. The quality of work is impressive.

The concerning part: scale. My best estimate is that only 1,000 to 3,000 people globally work on cooling interventions. That's absurdly small for what might be humanity's most consequential intervention. To put it in perspective, more people work at my local shopping mall than on potentially cooling the entire planet.

Each organization excels at its mission. But when you map the whole ecosystem, you notice what's missing.

The Advocacy Gap

No organization is making the positive case for cooling preparation.

I experienced this firsthand at the Global Tipping Points conference in Exeter. Four days of scientists describing civilization-threatening catastrophes—Amazon dieback, Atlantic circulation collapse, irreversible ice sheet loss. Yet in all those sessions, cooling interventions got maybe 60 minutes total. When I asked a climate scientist about it, he told me I wouldn't find support there because "geoengineering is just cover for the oil and gas industry."

This was eye-opening for me, and revealed the dynamics at play. The cooling research organizations doing excellent work have made strategic choices to maintain neutrality on whether or not we should eventually deploy—and I understand why. Advocacy would invite fierce criticism from the broader climate community, the kind I witnessed at Exeter. It's rational to focus on research and avoid that fight. The pattern mirrors early carbon removal resistance, when speaking positively about removal drew accusations of enabling fossil fuel companies.

But those strategic choices, however sensible, create an advocacy gap in the ecosystem.

The troubling part is that the absence of advocacy means we're not preparing for what the evidence suggests is likely necessary. We're treating cooling interventions as an abstract future possibility rather than something requiring active preparation.

I learned this lesson with carbon removal. Scientific papers alone didn't build the industry. It took organizations like Carbon180 pushing policy, advocates making the public case, and yes, companies like Nori painting a vision of what's possible. In early 2018, before the IPCC formally acknowledged negative emissions were required, we held a conference called Reversapalooza. We stood up and said: carbon removal is needed, it's possible, and here's how we're going to help build it. That kind of advocacy creates permission for action.

Without advocacy, there's no narrative building. No public engagement. No political permission to act when action becomes necessary.

What Advocacy Actually Means

Let me be clear about what advocacy means here. It doesn't mean rushing to deploy stratospheric aerosols tomorrow. It doesn't mean picking technological winners or ignoring very real risks. If research shows that SAI dangerously depletes ozone, then SAI is off the table. That's how science works.

Advocacy means acknowledging that temperature stabilization will likely be required and building readiness accordingly. It means creating trust infrastructure before we desperately need it. Building transparency systems so people understand what's happening. Engaging communities who've never heard of cooling interventions but whose lives will be affected. Making space for honest discussions about trade-offs and risks.

It means education—helping people understand not just the how but the why. It means collaborative development with regions and communities traditionally left out of these conversations. The Degrees Initiative recently convened Global South leaders in Cape Town for exactly this purpose. It means preparing governance and decision frameworks while we still have time to be thoughtful.

Most importantly, it means being honest with people. Our institutions have hemorrhaged trust by withholding difficult truths. The path to legitimacy isn't through careful PR management. It's through radical transparency about what we face and what our options are.

Embracing the Beautiful Mess

The Make Sunsets controversy perfectly illustrates what's ahead. Nearly everyone I spoke to in the cooling space has negative opinions about them. They worry about a "Russ George incident" that poisons the well against all cooling research. I understand those concerns.

There's a scene in the movie Charlie Wilson's War where Philip Seymour Hoffman's character shares a parable about the Zen master and the little boy. The lesson is "we'll see"—what seems good or bad today might turn out differently tomorrow. Make Sunsets might be souring people on cooling interventions. Or they might be generating important conversations that wouldn't happen otherwise. We'll see.

What I do know is that Make Sunsets represents our future: messy, contested, imperfect. There won't be optimal deployment scenarios with perfect international coordination. There will be countries competing to deploy first, companies selling cooling credits, activists protesting, and researchers scrambling to keep up. Their existence teaches us about the chaotic reality ahead.

This messiness isn't a bug to fix. It's the reality we need to accept and prepare for. Waiting for perfect consensus guarantees we'll be too late. We need to learn how to navigate the mess responsibly, not pretend it won't exist.

The cooling conversation will always be complicated. Different regions will have different impacts. Governance will be contentious. Attribution will be impossible. Public opinion will be divided. That's precisely why we need to start building the infrastructure for these conversations now, while we can still be thoughtful rather than reactive.

I came to cooling interventions reluctantly, hoping carbon removal would scale fast enough. It won't. The evidence points clearly toward needing temperature stabilization to give our other climate solutions a fighting chance. We can acknowledge this reality and prepare thoughtfully, or we can wait until crisis forces our hand.

I believe a path that includes cooling interventions gives us better odds. The positive case for cooling isn't that it's good—it's that it's necessary. And necessary things deserve honest, open preparation, not whispered discussions in conference hallways.

Yes, bad actors will try to use cooling as an excuse to keep polluting. That's exactly why we need thoughtful advocates shaping the conversation before they do. The potential for misuse doesn't eliminate the need—it makes responsible advocacy more urgent, not less.

Someone needs to say this publicly. More people need to join them. The scale of what we're discussing—potentially altering the entire planet's temperature—demands more than 3,000 people working in isolation. It demands advocacy, engagement, and the courage to have difficult conversations before they're forced upon us.

The positive case for cooling is simple: pretending we won't need it doesn't make it less necessary. It just makes us less prepared.

Read the previous articles in this series:

Break Glass, Cool Planet

Here's the unvarnished truth: We need to buy more time for carbon removal to scale, and that means we need global cooling interventions – soon. Not as a replacement for carbon removal, but as a bridge to give carbon solutions the runway they need.

The Risk-Impact Paradox of Global Cooling

This is part 2 in my series on global cooling interventions. You can find part 1 and an outline for the multi-part series here:

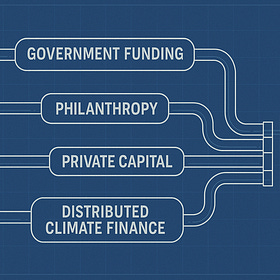

Who Pays to Cool the Planet?

When we kicked off the carbon removal industry, we had something (sort of) tangible to sell: a tonne of carbon removed. It has not been easy to build that market, but at least we had a unit. With global cooling interventions, we face a fundamentally different challenge. Who exactly pays to brighten marine clouds? What's the price for preserving an ice s…

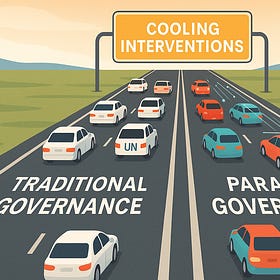

Climate Governance at Internet Speed

Right now, more than two dozen US states are considering bans on solar geoengineering research. Meanwhile, the Thwaites Glacier continues its inexorable march toward collapse, threatening meters of sea level rise that would reshape coastal cities worldwide. We're literally legislating away our emergency options while the emergency accelerates.

Hi Paul, thank you for this piece that was sent to me. Pity we missed each other in Exeter, we are definitely on the same team!

Onward!

Rob

Hello Paul,

Yes, totally agree with the need for cooling, thank you for sharing your message.

I wonder, what are your thoughts on the impact of restoring the living skin of the Earth (i.e. Walter Jehne’s synthesis, https://regenerate-earth.org/restoring-water-cycles-cooling-climate/) as a cooling process?

E.g. Vegetation transpires cloud-condensing bacteria and phytoplankton create dimethyl sulphide, another essential biologally created clound condensation nuclei, without which, our Earth’s albedo drastically decreases and our sensible surface heat dramatically increases?